Chapter Fourteen

–

A Magic Circle

Temple of the Rosy Cross

–

‘Just like that !!!’

I was more than a little surprised when the Knights Templar and Robin Hood turned up in my search for Shakespeare, but nothing could prepare me for connections to the worlds of Harry Potter, Paul Daniels, Patrick Moore and Mystic Meg, perhaps even Dan Brown and David Icke. Magic, alchemy, astronomy and astrology are all major components of Shakespeare’s work and so to have an expert’s knowledge of scientific principles, is just one of many pre-requisites the Bard would have needed, to write his entire canon of work.

Its worth pointing out, that at this stage in English history, the mystic arts of transmutation, alchemy and prediction of the future, were all wrapped up with the study of mathematics, geometry, human anatomy, the use of medicinal herbs, the mapping of the Earth’s surface and an understanding of the Heavens above. Astronomy, astrology, sorcery and science were all seen as one respectable discipline, by those who practised them, but regarded as satanic, by those who preached in a church, every Sunday, particularly if it was a Catholic church.

My growing picture gallery of paintings and drawings kept pointing me in the direction of scientific symbolism, making me realise that many of my leading literary and aristocratic figures were equally as adept in the alchemist’s laboratory, as they were in pontificating, at Westminster, or writing sonnets to their lovers. Several were master mathematicians, botanists, astrologers and astronomers, but often with a devoutly religious aproach. Their intent, perhaps part of a master plan, was to use their humanist skills to improve the world in which they lived, and to create a model, which could, potentially, guide the future of mankind.

Many new scientific theories were being developed in 16th century Europe, particularly relating to the Earth’s relationship with the Sun, but these new ideas left ‘Humanists’ open to accusations of heresy, as they conflicted with the religious teaching of the Roman Church. The punishment for heretics was fairly standard across Europe, the transgressor to be ceremonially burnt at the stake, with estimates of over 10,000 individuals being dispatched in this way.

Several of those involved in proclaiming the benefits of the new science met that fate, usually when they were too vociferous with their claims, or ventured into unfavourable pastures, those still controlled by the mighty Church of Rome. These innovative Renaissance scientists were regarded by the Papacy as magicians and sorcerers, and therefore devil worshippers and heretics. However, the Protestant rulers of Northern Europe saw things differently, and treated them in a more benevolent fashion, for they saw potential sources of enormous wealth. Just imagine all that rather boring looking rock and iron being transformed into bright, shiny gold.

Heavens above

The Digges family, previously, just a name attached to a poem, in the prologue to the First folio, now enter the story with some purpose. Leonard Digges was one of the more obscure contributors to the 1623 preface, but he was actually a member of a famous family of mathematicians and astronomers, and there is more than a passing connection to Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’.

In November 1572, a supernova, an exploding star, appeared in the night sky, in the constellation of Cassiopeia. Suggestions are that this is the star mentioned in the opening scene of ‘Hamlet’, by Bernardo, one of the soldiers on duty at Elsinore Castle. This astronomical event was initially visible, even in daylight, and was a feature of the night sky for over a year, before fading to nothing. Only in recent decades, using sophisticated imaging, have scientists proved the existence of this exceptional event. Shakespeare was just eight years old, when this celestial extravaganza was amazing the world.

This spectacular occurrence brought new energy to the already growing interest in science and astronomy, which had already preoccupied Renaissance Europe for nearly a century. The person who studied this celestial event most closely was Tycho Brahe, a 26 year old Danish scientist. The Danish astronomer was not the ‘nerdy’ boffin you might expect, as despite his insistence on total accuracy in all aspects of his work, his other major interest in life was swilling large quantities of ale, with his prolonged drinking sessions, often ending in a wild, drunken brawl.

There is a portrait of Brahe, engraved in 1590, encircled by his family coats of arms, and amongst the heraldic shields were those belonging to his cousins, Frederick Rosenkrantz and Knud Gyldenstierne, the names of two characters in Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’. These were the spies, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and their names translate, coincidently, into ‘rosy cross’ and ‘golden star’.

In 1576, Tycho Brahe built an observatory at Uraniborg, in the middle of Hven Island, situated in the Oresund channel, between Sweden and Denmark. Less than ten miles across the water, on the Danish mainland was Kronburg Castle. So, on a clear day, when Brahe looked out from his observatory, he could see the fortress, better known today as Hamlet’s, Elsinore Castle. Brahe wouldn’t have been the only one to make that observation, as he welcomed into his home hundreds of students, from all over Europe, all eager to learn more about the new discipline of astronomy.

One of the English astronomers who wrote about the 1572 supernova was Thomas Digges, father of Leonard, and he corresponded with Brahe about the event. A passage in ‘Hamlet’ seems to be taken from their scientific explanation of the cosmos, with the Sun being at the centre and everything else rotating around it, similar, but not identical, to the ideas proposed earlier by Nicolaus Copernicus.

‘Doubt that the stars are fire Doubt that the sun doth move’.

Hamlet; Act 2, Scene 2

This theory was against the accepted view of the Universe, which placed the Earth in the centre of everything, which is then surrounded by the Heavens, fixing the Earth in one place. Copernicus had already published his ideas of the Earth rotating round the Sun, but these were not accepted by either Church or State and so Brahe’s work was seen as groundbreaking, by leading political figures at the time. Indeed, it was well into the 17th century that these ideas came into generally acceptance. For this view of the cosmos to appear in a Shakespeare play was a challenge to perceived wisdom of the period and potentially be seen as blasphemous.

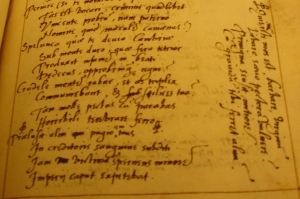

The son, Leonard Digges, also provides a link to one of the very few contemporary mentions of Shakespeare. There is an intriguing inscription, written by Digges, on the flyleaf of a book, which his friend, James Mabb, (another contributor to the First folio), had sent from Madrid to London, to their mutual friend, Will Baker, in 1613.

‘Will Baker: Knowinge that mr Mab was to sende you this Booke of sonets, which with Spaniards here is accounted of their Lope de Vega as in Englande we sholde ofor Will Shakespeare. I colde not but insert thus much to you, that if you like him not, you muste neuer reade Spanishe Poet.’

Lope de Vega was a prolific poet and dramatist and the comparison is being made that he is a Spanish version of William Shakespeare, the sonnet writer. The note was written four years after Shakespeare’s Sonnets had been published and so assumes that all three men were aware of the poems.

Leonard Digges used Edward Blount to publish his writing, and Blount was also a close friend of James Mabb. In 1622, they made it a foursome, when Digges and Ben Jonson contributed commendatory verses to a work translated by Mabb and published by Blount. The 1640 edition of Shakespeare’s ‘Poems’, also included verses by Digges, but this was five years after his death. Digges’ supportive verses refer to plays not poetry, so this contribution may have been intended for the 1623 or 1632 folios and edited out, but kept safe for later use, possibly by the Cotes printer family, who were involved in all these projects.

So, in 1622, Digges, Mabb, Jonson and Blount were very much an item, a team of friends helping each other, with their own projects. With Mabb also related to John Jaggard, as his brother-in-law, then it is easy to see how these same people ended up being involved in Mr Shakespeare’s compendium.

Leonard Digges father, Thomas, had the perfect scientific grounding in science, as he had been brought up and educated in the household of John Dee (1527-1608), who was the best known mathematician and scientist of the age. Dee became a close adviser to Queen Elizabeth and William Cecil, as well as receiving patronage from the Earl of Leicester and Philip Sidney. John Dee is a figure who has lurked in the shadows of English history, but he is about to take his fair share of the limelight.

What outwardly appeared to be a collection of theologians, scientists and mystics, became a front for a more secretive group, whose legacy goes back to the time of the Pharaohs and before that to the Sumerian culture of 6000 years ago. Many of these ‘Humanists’ were in reality, Rosicrucians, ‘Brethren of the Rosy Cross’, inheritors of secret knowledge, passed down to them from Sumerian, Egyptian and Judean traditions.

This knowledge was known as the ‘Hermetica’, and designed to enlighten the reader about the human mind, nature and the universe. The Hermetic texts, named after Hermes, the Greek version of the Roman god, Mercury, (the messenger), offered a medium for the works of Pythagoras, Plato, Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy and others, to become available to scientists and mathematicians of the Middle Ages. These texts also provided education and inspiration for architects, artists and writers of the period, but not all were kept secret as they had been, at least not after the advent of the ‘printed page’.

The very first book which transferred one of these ancient texts into print was the ‘Epitome of Ptolemy’s Almagest’. Originally a Greek manuscript, the ‘Almagest’ had survived in Arabic and Latin translations for over 1200 years. However, in 1460, Cardinal Johannes Bessarion commissioned the German astronomer, Georgius Peurlachius (died 1461), to translate his own copy of the Greek manuscript, to create an ‘Epitome’ or summary of Ptolemy’s work. After the ill-timed death of Peurlachius, the task was taken up by his student, Johann Regiomontanus, who planned to print the work on his own press in Nuremburg. Regiomontanus died in 1476 and it was a further twenty years before Johann Hamman, on 31st August 1496, published this ground breaking piece of scientific work.

Claudius Ptolemaios, (known as Ptolemy) (c90 AD–168AD), one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, lived in Alexandria, Egypt, during the period of the Roman occupation. In his ‘Mathematical Treatise’, Ptolemy claimed he had summarised the accomplishments of ancient Greek and Babylonian mathematical astronomy, so taking us back three or four millennia. Written in Greek, Ptolemy’s book was titled ‘Almagest’ (‘The Greatest’), by its Arabic translators, and is the only authenticated text on astronomy and trigonometry, which has survived from the ancient world to the present day.

The ‘Almagest’ was preserved, like most of Classical Greek science, in Arabic manuscripts, but had been translated into Latin, in Sicily and Spain, during the 12th Century, so would have been available to the early Portuguese explorers. The major flaw in the work was that Ptolemy’s model of the Universe, like those of his ancient predecessors, was ‘geocentric’, putting the Earth at the centre of the cosmos.

Ptolemy presented his astronomical models in convenient tables, which could be used to compute both the future and past position of the planets. There was a catalogue of forty eight stars, based on work by an earlier Greek astronomer, Hipparchus (190 BC–120 BC) and the text also offered practical methods for making celestial observations. It was the printed ‘Epitome’, which became the standard text for Hermetic education during the 16th and 17th centuries, succeeding the more cumbersome handwritten manuscripts and therefore, one that would have been familiar to our band of Rosicrucian scientists.

Title page of the ‘Epitome of the Almagest’ – 1496 – photo KHB

(notice that ‘Antarctica’(not ‘discovered till 1820) is named – in the correct place)

The aim of the Rosicrucians was to use this ancient knowledge, to create a perfect, unified world, one with a single religion and a single government, a ‘Utopia’. The word had been used by Thomas More, in his book of the same name, published in 1516, but the principles go back to Plato’s ‘Republic’, written 2000 years earlier. This proposed a rigid class system, with the leading socio-economic groups ranked as golden, silver, bronze, but with the majority of the population being given only ‘iron’ status.

Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ – 1516

Plato’s ‘golden ones’ were to be the ultimate product of a 50 year education program, creating an elite group of ‘philosopher-kings’, who would re-organise the world and in so doing, eliminate poverty and warfare. The ‘golden ones’ were an obvious template for the Rosicrucians, who came to regard themselves as the intellectual elite of the scientific world.

Essentially Protestant in their religious beliefs, the Rosicrucians also had liberal minded ‘Catholics’ and closet ‘Atheists’, such as Walter Raleigh, in their midst. Their dream was to create a ‘New World Order’, one that transcended the existing religious ideologies of Catholic Rome and the newly created, Protestant faith of Northern Europe.

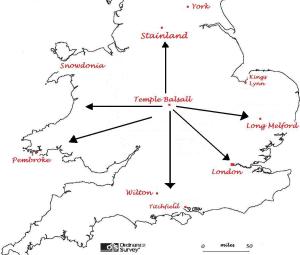

It has been suggested, that once the Rosicrucians realised their dream was never going to be possible, in a religiously divided Europe, they sought to create their ‘perfect World’, across the Atlantic Ocean, a pioneering venture which eventually became, the United States of America. All the evidence points in that direction, because the leading lights of Rosicrucian England were at the forefront in establishing the earliest colonies in Virginia, New England and Newfoundland, with followers of Rosicrucian ideals holding high positions in the fledgling colonies. Their descendants continue to run the show, today.

Another term to describe a perfect world is ‘Arcadia’, and that was the most famous work created by the Sidney literary circle, becoming one of the most popular and reprinted works of the 17th century. Philip and Mary Sidney’s ‘Arcadia’ also supplies the sub-plot for one of the Bard’s most famous plays, ‘King Lear’, regarded by many Shakespearean actors, as his greatest and most challenging work.

A further example of Utopian thinking was put forward by Francis Bacon, in his novel ‘New Atlantis’, published in Latin, in 1624 and English, in 1627. This described a world organised along Rosicrucian ideals, with peace, harmony and prosperity, being created by a new religion based on the use of science and advanced schemes of learning. Francis Bacon wanted to rebuild Solomon’s Temple in his new city, called Bensalem, the world centre for his new scientific developments. A generation later, Bacon’s work inspired the formation of the ‘Royal Society’, which provided a stimulating and safe environment for the ‘golden ones’, to create the foundations of our modern world.

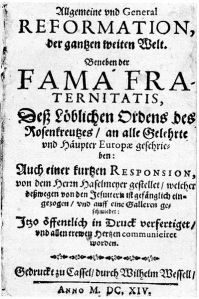

The Rosicrucians, the ‘Fraternity of the Rosy Cross’, officially announced themselves to the world in 1614, when an anonymous pamphlet titled ‘Fama Fraternitatis’, was published in Kassel, a Calvinist stronghold, in Hesse, close to the centre of the state, we now call Germany, This pamphlet was followed by another, ‘Confessio Fraternitatis’, in 1615, and finally, in 1616, an allegorical play, the ‘Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz’, arrived on the scene. They all tell the story of a long lived alchemist, who made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and during his return, discovered the ancient secrets of science and mathematics. The traveller, ‘Christian Rosy Cross’, learnt these secrets from the wise men of ‘Damcar’, in Arabia, whose knowledge could be traced back to the early civilisations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. ‘Damcar’ has not been identified, but has claims as a legendary city that was the repository for all the secrets of civilisation, a claim also made by the Royal Library, at Alexandria.

This mythical man, Christian Rosenkreutz, was said to be 106 years old when he died, in 1484, and he is supposed to be the founder of the Rosicrucian Fraternity. The three proclaiming pamphlets, written originally only in German and Latin, told of a secret group who were preparing to mobilise the ‘intelligencia’ and ‘philosophers’ of the Renaissance, into a political force and transform Europe from a medieval world, dominated by the word of the priest, to a new world, dominated by science.

Despite this public launch in 1614, there is great difficulty in identifying specific individuals, as being Rosicrucians, because of the secrecy surrounding the order. The ‘Fama Fraternitatis’ states they should not be distinguished by their dress, should meet annually in the ‘House of the Holy Spirit’ and that each member should choose one man to succeed him. Rosicrucians were also expected to use their medical skills to treat the sick, free of any charges.

However, this openness to public scrutiny only lasted three years, because at a meeting in Magdeburg, Lower Saxony, in 1617, there was agreement that the order should return to their covert existence and remain so for 100 years. Magdeburg, in the very heart of ‘Germany’, was a major town in medieval Europe, setting a standard for law-making, which spread across central and eastern European states.

However, like all secret societies, the membership must have had a way to identify other members and communicate with each other. This they achieved with their symbolism, which has now permeated everywhere into society, although most people are oblivious to this today, as the shapes and objects are seemingly commonplace. However, if their major goal was to transform society through science, then the results of their exploits should be plainly visible and, therefore, offer clues to their identity. Once one of their group is identified, then friends and family of that individual, offer the best clues to tracing their sphere of influence, and uncovering their network of members.

Rather like the Knights Templar, who have been confined, by the modern day intellectual elite, to the medieval history books, the Rosicrucians are said, by 21st century ‘experts’, to be just a ‘short lived, 17th century sect’, whose main aim was transmutation of base metals into gold. ‘Official’ histories of this secretive body, and its more famous cousin, the Freemasons, lead us to believe that there was a discontinuity of more than three hundred years between the Knights Templar disappearing in 1312 and the other secretive groups making themselves public, in 1614 and 1717. The wider that time gap appears to be, the less reason there is for the general population to join the dots together.

Establishment historians seem desperate to make the general public believe that the present day leaders of western society are NOT directly descended from this earlier incarnation of knights, scientists and theologians. Modern histories rarely mention that most of our great literature, great inventions and great buildings were created by this group of Rosicrucian, ‘golden philosophers’. The grandest architecture of London and church architecture elsewhere in Britain, even the humble red telephone box, were all the creations of descendants of the ancient traditions.

The credibility of those that claim there is a significant time gap between these old and new traditions has been exposed by the discoveries at Rosslyn Chapel, in Scotland. This is a building extravagant in the extreme, and contains overt examples of both the Knights Templar and Masonic traditions, in a period when neither is supposed to exist. Rosslyn church and castle were rebuilt by the Sinclair family, who were originally Norman knights called St. Clare, and have already been mentioned because of their ancestral link to Hugh de Payens. It has even been suggested that Templar leader, Hugh married a daughter of the St Clair family, whilst ‘coincidently’, the name Rosslyn, a corruption of the name ‘Roslin’, means ‘beautiful rose’.

Those that knew the secrets of the Hermetica trusted no-one except themselves, and so this Rosicrucian movement was not one designed to attract mass support. Their intention was to change the world from the top downwards, using the Gold Medal winners to lead the way, but the dilemma for the Rosicrucians was that although they wanted to spread their scientific knowledge, using the new invention of printing, the very fact that their words had a degree of permanence on the printed page, might turn out to be their Achilles heel.

Ring-a-Roses

Symbolism was a key part of the Rosicrucian methodology and it developed as a two handed weapon, both to spread the word and to protect the identity of the promulgators. Their published work was always released anonymously, or using pseudonyms, known only to the inner circle of the brotherhood. Rosicrucians also needed sympathetic friends in the publishing business, who would help preserve their anonymity. Clues to unravelling the complicated web they weaved are to be found in the distinctive symbols of the printing industry.

The symbol of the rose is now common place in Britain, as the Tudor rose adorns so many of our old stately homes, churches and public buildings. The adoption of the rose, by the Tudor monarchs, was said to signify the union of the red and white roses of York and Lancaster, at the end of their civil war.

Tudor Rose, created by Henry VII in 1485

The white rose of the House of York, had the earliest origins of the two, and can be traced back to the early crusader days, in the Holy Land. In reality, the Wars of the Roses resulted in the unification of two branches of the Knights Templar, who had been bickering over their right to the English Crown for close to a century. Could it just be a pure coincidence that the Tudors and the Rosicrucians used the same rose symbol, drawn in an identical way?

An almost identical rose symbol was used as a personal seal, by Martin Luther, one of the founders of the Protestant movement, who was active in Germany, in the early part of the 16th century. There seems to be no logical reason why Luther should adopt the same emblem as the Welsh Tudor King, who pre-dated him by a generation, with their homelands located hundreds of miles apart.

Personal mark and ring seal of Martin Luther

Luther’s seal displays other interesting symbols, which link to the Hermetic movement, joining science with the new religion. Another institution to make use of the same emblem was the Stationers’ Company, based in London, who also used an identical motto, to that of Martin Luther and the Lutheran Reformation. The link between Protestantism and the printing industry is quite clear.

Stationers Company emblem and motto (‘verbum domini manet in eternum’, the word of the Lord shall remain forever.)

One of the first members of the European Renaissance movement, thought to be able to control these mystical, Hermetic elements, was Philippus von Hohenheim (1493-1541), known more commonly as Paracelsus. He was a German speaking, Swiss alchemist, whose expertise included the diverse studies of medicine, botany, mathematics, astronomy and astrology. His portraits usually show him holding a sword with the word ‘Azoth’, inscribed on the handle, and inside the hilt there was a secret compartment, which contained his magic red powder, which he believed could cure all sickness, his panacea for all the ills of mankind.

‘Azoth’ is the ancient word for mercury and the substance was regarded as a panacea, for curing all disease, and thought to be the base ingredient of all matter. Alchemists believed that understanding the secrets of mercury made transmutation from base metal to gold, a viable goal. Indeed, during their 16th century, those successful South American adventurers, the Spanish, used mercury to help extract silver from the powdered ore, poisoning thousands of native slave-workers in the process.

The symbol for mercury is another old friend, the caduceus, or rod with entwined snakes, which was later adopted by the medical profession, the Order of Freemasons, part of the printer’s mark of Johanne Froben, Andreas Wechel and William Jaggard, the Eliot Court printing house and appeared on the frontispiece of Shakespeare’s 1664 folio. You follow my drift..???

Paracelsus was an outspoken man, who put curing disease at the top of his, ‘to do’ list, and above his gold making or astronomical aspirations. He believed that illness was caused by poisons and that a cure could be affected by using other toxic substances, but in a controlled manner, a belief that underpins holistic medicine today. Mercury (azoth) is now known to be highly toxic, but had been used by the Hospitaller knights as an early treatment for the Bubonic plague. They used mercury as an ointment, rubbed on the flaming pustules of the skin, and that is why it became widely used as a treatment for syphilis, as many of the symptoms were similar.

When an effective treatment for syphilis was finally discovered, in 1910, it was not too dissimilar, a measured dose of a compound derived from the toxic poison, arsenic. This proved to be the very first modern chemotherapeutic agent and shows that the theories of Parcelsus were along the right lines.

It is suggested that Parcelsus was the first true Rosicrucian, as his work was often referred to by later Hermetic and Rosicrucian disciples. He may have been one of the first to openly preach the works of the Hermetica, but he was certainly not the first to have access to the ‘secrets of the ancients’. One aspect of his work that reflected the Renaissance thinking, was his rejection of the mystical side, (wizardy and magic), instead, concentrating on scientific experiments, an approach that wouldn’t be out of place in a school chemistry laboratory today.

The English equivalent of Parcelsus came a generation later, in the shape of Dr John Dee (1527–1609), a mathematician and alchemist. John Dee had close relationships with all the great figures of the day, including Queen Elizabeth and her close advisors, the Cecils, Walsingham, Robert Dudley and the circle of Philip Sidney. He tutored most of them and his status, as the leading Hermatic scholar of England, also allowed him to play an influential role in Elizabethan politics.

John Dee’s expertise and beliefs stretched from pure science to pure occultism, and these two ends of this scientific continuum were indistinguishable to him and some of his most ardent pupils. Things remained that way until science and magic began to diverge, at the beginning of the 17th century, at a time when Dee’s influence began to wane.

Dee was a devout Christian, but also believed in Hermetic and Platonic doctrines, which were principally governed by a reliance on numbers. His practical use of mathematics and geometry enabled him to become an expert in navigation and he supplied training for many of the early oceanic expeditions, including those of Walter Raleigh, Humphrey Gilbert and Francis Drake. His name is mentioned alongside all the leading characters in this Shakespearean saga and so it is no surprise that the Bard’s plays owe much to the scientific discoveries of the times, many inspired by John Dee.

History, though, has not treated John Dee well, because he is probably best known today, as the man who ‘conversed with angels’. Yes, Dee never forsook the mystical end of the spectrum, recording his conversations with ‘heavenly angels’, in his extensive diaries, always seeking advice from his angelic friends before making an important decision. Dee even invented a new language, called ‘Enochian’, which he and his partner, Edward Kelley, used to record these mystical conversations.

This aspect of his research brought him scorn from his contemporaries, and has not endeared him too well to modern scientific opinion, who suspect, although cannot prove, that there is no such thing as an ‘angel’. Only in more recent times, thanks to the work of 20th century historian, Frances Yates, has Dee’s work been positively reassessed, and given a reasoned place in the history of science. Remove the fantasy surrounding John Dee, and you are left with some high quality scientific research.

John Dee was another who had Welsh origins and it is speculated his family arrived in London, with the Tudor entourage of Henry VII. Perhaps, he was from the same family of Welsh wizards, who could count Merlin amongst their number. Several Welshman crop up in this section as possible Rosicrucians, and so the influence of Welsh people on the modern history of Britain, needs to be given a little more prominence.

In 1564, John Dee published his seminal work and with it his most famous visual legacy, the ‘Monas Hieroglyphica’. He stated that his symbol represented a ‘Crescent Moon above an Earth circling the Sun on top of a Cross with a fiery furnace below’, and was Dee’s vision of the unity of the Cosmos.

It was a symbol that has only been given limited airtime, since he first created it, but suddenly and in totally unexplained fashion, it became the most unlikely, cuddly, mascot figure, found on the streets of London, during the summer of 2012. They were a ‘must have’, for every child visiting that summer’s ‘gold medal making’ festivities. ‘Think on’ – as they might say in darkest Yorkshire.

John Dee’s ‘Monas Hieroglyphica’

The book, which accompanied the launch of the ‘Monas’ symbol, offered an explanation of his theories, but John Dee also organised his own ‘road show’, where he was able to debate his ideas in more detail. In an extensive tour of Eastern Europe, Dee travelled as far as Hungary, to present a personal copy of his ‘Monas Hieroglyphica’, to Maximilian II, the Holy Roman Emperor. Was this the first ever book-signing tour?

Later version of the Monas, published by the Wechel family in Frankfurt, in 1591

John Dee is reputed to have been elected as the English Grand Master of the Rosicrucians, in 1550, taking over from Sir Francis Bryan…!! Yes, the appearance of Francis Bryan, on a list of leaders of a secret group of scientists was somewhat of a surprise and has particular significance, as he has links in this story to the Neville family, Henry VIII, and perhaps, more crucially, to the Jaggard printers.

John Dee is then thought to have passed his title and scientific responsibilities on to Francis Bacon. Although no-one has found John Dee’s membership card to the secret societies, everything points in that direction. In 1576, he wrote the ‘History of King Solomon, his Ophirian voyage, with divers other rarities’, voyages which had connections with King Hiram of Tyre, who helped Solomon to build the Great Temple at Jerusalem, a focal point of Masonic beliefs. This seems to suggest that the Rosicrucian and Masonic movements had much in common, even if they kept their identities separate.

In 1571, John Dee travelled to Lorraine in France, under the warrant of Lord Burghley, to acquire alchemist’s equipment for Henry Sidney and his wife Mary Dudley. Everyone needed a Royal license to travel or to import alchemist materials or, indeed any chemical substances. Salters, like James Peele and later Abraham Jaggard, were merchants who held licenses to trade in such goods.

During the period 1567-81, Dee had, as his personal assistant, Roger Cooke, grandson of Anthony Cooke, and therefore one of the Cooke humanist clan. Roger Cooke, later, took his alchemy skills to Europe before returning home, to work as an alchemist for the Countess of Pembroke, at Wilton House.

In 1583, Dee met the visiting Polish nobleman, Count Albert Alasco, mentioned earlier as guest of honour at William Gager’s theatrical event, in Oxford. Alasco seems to have been invited to England because of his reputation as a wealthy patron and practitioner of alchemy, but his visit had the trappings of a state visit, by someone of much greater importance. He was received by the Queen and Robert Dudley, at Greenwich Palace, prior to his week long visit to the university town.

The whole event appears to have had a much deeper purpose, as the list of attendees, the program of events and high costs involved, indicates this was no ordinary visit by a Polish nobleman. In reality this may have been a joint meeting of the Hermetic and Rosicrucian elite of England and Europe, perhaps one of those, ‘required’, annual meetings, mentioned in the ‘Fama’ text.

Alasco befriended John Dee and his fellow English ‘magician’, Edward Kelley, inviting them back to Poland, but on their arrival the Count proved to be not as wealthy and influential as he boasted, and the two Englishmen quickly deserted him. Instead, they visited other Hermetic practitioners in central Europe, including a meeting with the astronomer, Tycho Brahe, in Vienna.

John Dee recorded these foreign adventures, in his meticulous personal diary, which he kept, from 1577 till 1601, and this is where notes of his angelic visitations were kept. From his early years, onwards, Dee assembled, at his Mortlake home, one of the finest libraries in Europe.

When he returned to England, in 1589, he found his library was in a state of ruin. There is a story that his house was ransacked, but the books may have been sold during his absence, by his brother-in-law, who rented the house. Many of Dee’s books and papers have turned up subsequently, in university libraries and other academic institutions, so they were not burnt by religious extremists, as some accounts suggest.

Queen Elizabeth had been Dee’s keenest supporter, but when she died in 1603, King James, turned out to be a non-believer in the occult, dispensed with both his mystical and navigational services, and so the Rosicrucian view of the world faced a major set-back. There is even a theory, that the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was inspired and organised by the ‘Fraternity’ and was not primarily a Catholic revolt after all. The earlier revelations about Lord Carew, Robert Cecil and the failure to account for six tons of gunpowder might help fuel that discussion.

Dr John Dee finally died, disgraced and in poverty, in 1609.

Much of this information about John Dee, comes from the work of Frances Yates (1899-1981), a historian, who wrote extensively about the Hermetic tradition of the Renaissance. She tried to explain and make sense of the Rosicrucian traditions, which only made the headlines, for a decade in the early 17th century, before being confined to the ‘secret box’, for the next four centuries.

Her three books ‘Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition’ (1964), ‘The Art of Memory’ (1966), and ‘The Rosicrucian Enlightenment’ (1972), opened the door to understanding more about this crucial period in world history, at the dawn of the modern era. There is still much more to be discovered and her pioneering work has not been advanced very far, by others, in the past 40 years.

Evidence of the Rosicrucian link to John Dee, is embodied in the use of his ‘Monas’ hieroglyph, prominently displayed at the beginning of the allegorical play, ‘The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz’, a religious story set over the seven days before Easter, in 1459.

‘Coincidently’, it was in 1459, that a group of real stone masons, first met in Regensburg, and it was on Easter Day in 1464, that the Constitution of the Masons of Strasbourg was approved and signed….!

Regensburg is a major Bavarian town, on the confluence of the Danube and the Regen rivers, with a magnificent stone bridge and a fine Gothic cathedral. It has particular significance because in 1096, on the way to the First Crusade, Peter the Hermit, led a mob of Crusaders that attempted to force the mass conversion of Regensburg Jews, killing all those who resisted. Again we have a significant time and a significant place that ties diverse parts of my story together.

The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz’

‘This day, this day, this day The Royal Wedding is. Art thou thereto by birth inclined, And unto joy of God design’d? Then may’st thou to the mountain tend Whereon three stately Temples stand, And there see all from end to end’

The mention of three Temples on the mountain, is obviously referring to Jerusalem and the subsequent section has more than a hint of the early Knights Templar and later the Masons.

On the last of the seven days, Christian Rosencreutz and the other guests are made Knights of the Order of the Golden Stone and the rules of the Order were read out to them.

- The Order shall always seek its origin in God and nature, and never the demonic.

- The knights shall repudiate all vices and weaknesses.

- They shall stand ready to assist all who are worthy and in need.

- The honour of the Order shall not be used for worldly gain.

- The knights shall be ready for death whenever providence decrees it.

Another total surprise to me was that the ‘Monas hieroglyph’ also provides a link to John Winthrop, one of my previously fringe characters in this story; who was the leader of the 1630 expedition to Massachusetts and who chose William Gager to be the physician for his expedition His son, John Winthrop, junior, became a leading disciple of the Hermetic tradition and thought it his life’s work to develop Renaissance scientific thinking in his new homeland of Massachusetts. Winthrop junior, used Dee’s ‘Monas’, as his own personal symbol and this continued, through to his son and grandson.

Winthrop junior, returned to England more than once, first to gain rights to extend the colony and later he became enrolled, as one of the early members of the Royal Society. Two generations down the line, John Winthrop (1714 –1779) was Professor of Mathematics and natural philosophy at Harvard College. He was also a distinguished physicist and astronomer and one of the foremost American scientists of the 18th century, corresponding, regularly, with members of the Royal Society, in London.

This trans-Atlantic connection also offers credence to the idea that America was, indeed, intended to be the new ‘Utopia’, ‘Arcadia’ or ‘New Atlantis’, that the Rosicrucians were seeking to create. Many of the rich men involved with this Shakespeare story, were also the same ones that supported the brave pioneers, who were seeking a new life, in New England and Virginia. These migrants were almost exclusively Protestant adventurers and religious refugees who hailed from the Rhineland, the Low Countries and the South and East of England.

Two other symbols, which are highly significant in the Rosicrucian world, are the Eagle and Pelican, sometimes combined with their familiar, Rose and Cross.

The pelican emblem on this decoration is remarkably similar to the printer’s mark of royal printer, Richard Jugge, and later utilised by Scotsman, Alexander Arbuthnot. In 1579, Arbuthnot was commissioned to print a Bible for every parish in Scotland, for a fee of £5 each. Printing Bibles is obviously one connection between the two men, but there seems to be more.

Albert Pike (1809-1891), American Confederate officer, writer, and noted member of secret societies, explained the meaning of the Rose, Cross and Pelican, in 1881.

‘The Rose is a symbol of Dawn, of the resurrection of Light and the renewal of life, and therefore of the dawn of the first day, and more particularly of the resurrection: and the Cross and Rose together are therefore hieroglyphically to be read, the Dawn of Eternal Life. The Pelican feeding her young is an emblem of the large and bountiful beneficence of Nature, of the Redeemer of fallen man, and of that humanity and charity that ought to distinguish a Knight of this Degree.’

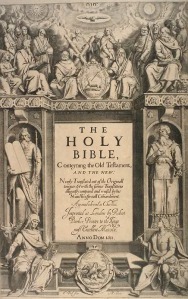

The Pelican symbol also has religious connections with rebirth, and is linked by some Christian groups, to the resurrection of Jesus. Others connect the pelican symbol with ‘charity’, as the pelican mother might draw blood when feeding her young. The pelican even made it to the front cover of the King James Bible, (1611), as did the ‘lamb and flag’ symbolism of the Middle Temple.

Shakespeare makes two mentions of pelicans using their blood for re-birth.

Hamlet

To his good friends thus wide I’ll open my arms

And, like the kind life-rend’ing pelican,

Repast them with my blood.

Richard II

O, spare me not, my brother Edward’s son,

For that I was his father Edward’s son;

That blood already, like the pelican,

Hast thou tapp’d out and drunkenly caroused.

Sometimes the Phoenix replaces the Pelican as a symbol of rebirth, and that mythical bird’s name has already appeared in this story, notably, the ‘Phoenix Nest’ and the ‘Phoenix and the Turtle’. Before leaving these two symbols, it is worth noting that two of the most famous and highly decorative portraits of Queen Elizabeth are known as the Pelican portrait and the Phoenix portrait, both painted by Nicholas Hilliard, in about 1576. The birds were worn as a brooch in the centre of each portrait and the Tudor Rose, as you would expect, also figures prominently in both portraits.

–

The Rosicrucians play ‘hide and seek’

The formal announcement of the actual existence of a group known as the ‘Rosicrucians’ was made in the German town of Kassel, in 1614, but it was only two years later, that English physician, Robert Fludd (1574-1637), published an explanation for the existence of the ‘Rose Croix’, in England.

‘Apologia compendiaria, Fraternitatem de Rosea Croce suspicionis et infamiæ maculis aspersam, veritatis quasi Fluctibus abluens et aspersam’

‘Compendium of Apology for the fraternity of the Rose Cross, to wash away the stains of suspicion and infamy’.

(Note: ‘apology’ means a ‘considered response’, not the modern, ‘grovelling’, use of the word.)

Fludd wrote in Latin, therefore, still aiming at the educated classes, so this was not something for the average pleb to worry about. ‘Establishment’ historians usually suggest his overt ‘apology’, proves Fludd definitely wasn’t a member, although his occupation of ‘physician’, probably gives the game away. It is also suggested by some conspiracy theorists, that Fludd was the 15th Grand Master of the Priory of Sion, a mythical order postulated in late 20th century fiction. (Dan Brown alert here..!)

Robert Fludd, another graduate of St John’s College, Oxford, was a remarkable man, discovering the circulation of blood, prior to William Harvey’s treatise, in 1628, and writing ground-breaking works, about perception and memory. Fludd had close associations with Francis Bacon and the pair has been suggested as co-founders of both the Rosicrucian and Freemasonry orders.

Too late in the day for that honour, I think..!

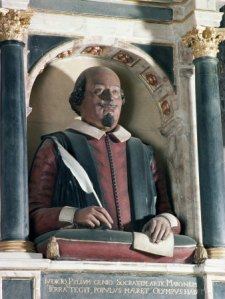

Robert Fludde

A significant individual, who connects the Rosicrucians to Philip Sidney’s circle and the University of Oxford, is Giordano Bruno (1548-1600). Frances Yates wrote a whole book about this Italian Dominican priest, who was a significant character in progressing Hermetic ideology. Bruno came to England in 1583, was present at the Alasco event and lectured and debated his ideas, at Oxford.

This brought criticism from traditionalists, within the Protestant church, notably the Bishop of Oxford and George Abbott, the Guildford grammar school old boy, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. Bruno’s co-debaters, in particular, ridiculed his crazy idea that the ‘Earth went round the Sun’. His aim, though, was to reconcile the rift between Protestants and Catholics, to re-form them into one new church. This view was rebutted in England, by those two extremists, the Catholics and Calvinists, a rejection which eventually lead to his fiery end, in Rome.

Whilst in England, Bruno had six of his works printed by John Charlewood, the same man whose business and wife ended up in the hands of James Roberts. Two of Bruno’s books were dedicated to Philip Sidney, who he had first met at the Oxford event. Bruno also worked with the mathematician and astronomer, Thomas Digges, and it would seem that all the noted ‘philosophers’ of the day, met Bruno, at some point, during his stay in England.

The most significant of Bruno’s works, one that links many of my leading players together, is ‘La Cena de le Ceneri’, commonly known as the ‘Ash Wednesday Supper’ (1584). Written in Italian, it describes a dinner party held with a group of English sympathisers, at the home of Fulke Greville. Definitive analysis of the identity of those involved is difficult, because Bruno used pseudonyms or other cloaking devices. The book, probably, summarises a number of meetings with friends and not one specific event.

Bruno spent two years in England, (1583-85) where fellow Italian, John Florio, was one of his friends, with Matthew Gwinne, Philip Sidney and Fulke Greville making up other close acquaintances. Bruno was also introduced, by Gwinne, to Thomas Sackville (Lord Buckhurst) and visited his London home. Buckhurst later became Chancellor of Oxford University and in 1599 was appointed Lord High Chancellor, in 1599. He was also a dramatist, of note, being the author of Gorbudoc, the first play written in blank verse, and one of the first to add political piquant, to his poetry.

Bruno left England and travelled to Paris, and eventually in 1591, was invited to Frankfurt, by Andreas Wechel, him of the printing family, to meet other like-minded thinkers. However, his reputation went before him and the Frankfurt town council banned Bruno from the precincts. So instead, Wechel arranged for his guest to stay at a nearby monastery, an action that had fatal consequences.

He moved on to Venice, but in 1593, he was charged with heresy, imprisoned for seven years and in 1600, was transferred to Rome, where he was publicly burnt at the stake in Rome’s ‘Campo de Fiori’, where a statue to him now stands. One of his main accusers was a priest from that Frankfurt monastery, where he had stayed, ostensibly, as a safe haven.

Bruno’s statue in Rome –

The statue dates from 1889 and continues my theme of a strong connection with the secret societies. The sculptor was Ettore Ferrari, Grand master of the Grande Oriente d’Italia, who were strong supporters of the unification of Italy, with the statue unveiled on June 9, 1889, where the radical politician, Giovanni Bovio, gave a speech surrounded by 100 Masonic flags.

Matthew Gwinne (1558 – 1627) was a physician, and another of Welsh descent. Son of a grocer, he followed what seems a familiar educational path, to Merchant Taylor’s School and then St John’s College, Oxford, where he became a Fellow. Some of you might notice a pattern developing here..!!

Gwinne became a major figure at Oxford, taking a lead role in a debate during the Queen’s visit, in 1592, and he succeeded William Gager as the chief organiser of plays for the university. Gwinne was also one of those who contributed to the Philip Sidney memorial anthology, in 1587. Gager and Gwinne seem to have been friendly rivals in the genre of neo-classical Latin authorship.

Gwinne was the physician, who became involved with another of my erstwhile fringe characters, when he accompanied Henry Unton, in his final stint as ambassador to Paris, in 1595. After Unton’s death, in 1598, Gwinne was appointed Professor of Physic, at Gresham College, a post he held until 1607. He had diverse literary connections, contributing commendatory verse to John Florio and working with him, on his major translations. He also worked with Fulke Greville on an early re-working of Philip Sidney’s ‘Arcadia’, which was halted, probably by the Countess, and never made it into the bookshops. Gwinne was certainly one of the anonymous ‘names’ involved in Bruno’s ‘Ash Wednesday Supper’ and he is someone who has to be taken seriously when the Shakespeare cards are finally laid on the table.

Giovanni (John) Florio (1553–1625), was an Italian who had a major influence over several characters in my story, and (shock, horror), has even been suggested as a possible author of some of Shakespeare’s plays. His father, Michelangelo Florio, had been a Franciscan friar, living in Tuscany, before converting to Protestantism, a decision which forced him to flee Italy, for London.

Michelangelo Florio’s more interesting connections now appear, because, in 1550, he was appointed as pastor to the Italian Protestant congregation of London, and for a short time served as a member of the household of William Cecil. The elder Florio then became Italian tutor to Lady Jane Grey and to Henry Herbert, who he praised as being his best two pupils.

Father and young son, John Florio, fled to Strasburg during the Marian period, but it was only John who returned to England, in the late 1570s, a journey that was to have a major effect, both on English literature and the manners and etiquette of the upper reaches of English society.

John Florio saw his role in England as a cultural ambassador, attempting to civilise those aggressive, uncouth Anglo-Saxons. He was a great reformer of English social etiquette, making bold attempts to improve both the behaviour and the language of his aristocratic friends. He was an advocate of the teachings of Bruno, and was very much a member of the Oxford University circle. Florio’s sister, Rosa, (nice name) married the poet Samuel Daniel, tutor to the young Herberts. Here we have that man Daniel showing his face, again, rather unexpectedly..?

In 1578, Florio dedicated his first published work to Robert Dudley, offering copious examples of the Italian use of proverbs and witty sayings, aimed at improving everyday discussion amongst the frothy gallants of the Royal Court. In 1591, he published a selection of dialogues in English and Italian, which contained over 6000 Italian proverbs. Florio’s input to the previously, rather pedestrian, English language was massive, and the richness of late Elizabethan literature owes much to his influence.

John Florio (1553-1625)

John Florio lived, for some time, in the home of the Earl of Southampton, at Titchfield Abbey, where he acted as a tutor to the young Earl. This was around 1590, soon after Southampton had left Cambridge University and had enrolled as a law student at Gray’s Inn. Florio was also a good friend of William Herbert, and left him money in his will to care for his sister, Rosa.

Under new management, King James I appointed Florio, as French and Italian tutor to Prince Henry, created him a ‘Gentleman of the Privy Chamber’, and he also became language tutor to Queen Anne. Florio published an updated English-Italian dictionary, which he named in honour of the Queen. He died in poverty, in 1625, another to disappear at the time of the First folio, but his daughter married well, her descendants becoming Royal physicians to later English monarchs.

So Florio and Bruno were two learned gentlemen from Italy, who brought great influence to bear on the gestating English language and its dependent culture. John Florio in particular seems to have had a massive influence on the flowering of English in both its written and spoken forms, and if we need to find a precursor to the great wealth of creative language brought to us by the works of Shakespeare, then surely the starting point must be John Florio.

The Italian is thought to have added nearly a thousand new words to the English language and his presence on the scene might explain how over 2000 new words and hundreds of new phrases suddenly appeared in the Bard’s work.

Ten of the Bard’s 36 plays had Italian roots and it does seem remarkable that our greatest writer is credited with a third of his output being based in a country, he supposedly never ever visited.

Was the real William Shakespeare possibly an Italian in disguise?

–

–

Chapter Fifteen

Italia Festa – (with a little French dessert)

Frescos and salt sellers

Shakespeare scholars have long marvelled at the Bard’s incisive knowledge of Italy, and to a lesser extent, our traditional enemy – those arrogant Frenchmen. The Italian theme was taken up by the Shakespeare Authorship Trust, for their 2013 meeting, held at London’s, Globe Theatre, and convincing arguments were made that suggest the author of Shakespeare’s Italianesque plays, must have had close-up and personal knowledge of the boot-shaped peninsular.

A year later, the 2014 gathering of the ‘doubtful’, again at the Globe, spent the day looking for a French Connection to the Bard, and whilst the detective work in discovering a Francophile link, turned out to be a little more complex, there is clear evidence, amongst some of the best known plays, that the author must, also, have had first hand experience of life in France, and the French Court in particular.

However, there is an obvious contrast between the Bard’s use of Italy and France in his plays. In Italy, the emphasis is placed on describing people and places, to impart a Mediterranaean atmosphere into the text, with plenty of olive groves, marble statues and frescos. Italian names, given to his characters, are everywhere too, cropping up in several plays, where they might be least expected.

The connections to France are far less obvious and lay just below the surface, with the turbulent politics of the religious civil wars, being the driving force behind the Bard’s plot lines. The French connections are clear and unequivocal, and the evidence is not even new, although it took a number of Frenchmen in the first half of the 20th century, to find it. However, since then, English followers of the Shakespeare debate, have seemed content to let their evidence fade into the mists of a Monet lily pond.

Stratfordians have long explained these foreign additions by contemplating the idea that their hero gained all the necessary information by paying regular visits to a number of English ‘libraries’. They earnestly suggest that English translations of Italian geography and botany handbooks were lying around in the reading rooms of Warwickshire country houses or on the bookshelves of the London publishing fraternity. Alternatively, they suggest that this detailed information could have been freed from the mouths of Italian merchants, over a tankard of mead or a glass of Tuscan wine, in the Mermaid Tavern or similar convivial establishments, which Shakespeare is ‘known’ to have visited.

The Italian angle is more straightforward than the French, as ‘Shakespeare’ has added specific details of Italian life, to add colour and vibrancy to ‘his’ plays. Stratfordians do not dispute this, but say this extra patination to the plays was just a figment of the Bard’s vivid imagination. To prove this ‘detail’ was imagined, they say he was just teasing his audience, with overt, geographical and historical errors.

‘Everyone knows’ that Milan is in the heart of the country and so has no trading port with the outside world, whilst it certainly never had an Emperor as its ruler.

Wrong and wrong again the Stratfordians say..!! Ah, yes, but……..

‘Romeo and Juliet’, ‘Merchant of Venice’, ‘Two Gentleman of Verona’, ‘Othello’ and the rest of his Italian catalogue, are actually based on real places, real physical geography, and real local history. The plays include observations of buildings and works of art that were unlikely to have been found, illustrated, in the reference section of the Stratford ‘Public’ Library…. (ha ha)

Stratford public library – literally, next door to Shakespeare’s old home in Henley Street…

So much detail can only lead to one conclusion, that the author of these ‘Italian’ plays had seen the sights for him or her self, or, as I think far more likely, for themselves.

American researcher, Richard Paul Roe, spent a significant portion of his later life, chasing down these detailed clues and with a great degree of success. He found there were sycamore trees in Verona, where Shakespeare said they would be, and to the surprise of many learned Stratfordians, he discovered that the best way to travel around northern Italy, during the 16th century, was by ‘barque’, on the extensive system of inland waterways, and yes, the Holy Roman Emperor did make a brief and unheralded visit to Milan, just the once. Roe also used the detailed directions given by ‘Launcelot’ to ‘old Gobbo’, in the ‘Merchant of Venice’ to discover the exact location of Shylock’s Venetian pent-house, a building which still exists today, next door to the ‘Banco Rosso’ – a derelict bank now a museum – Where else would it be?

Another major discovery is noted by Roger Prior, in linking a fresco in the town of Bassano del Grappa, 40 miles north from Venice, to a scene in ‘Othello’. Again the detail is such that it would seem highly likely that the author of this play, had seen the fresco themselves – again up close and personal.

The painted wall was on the front of a house, in the ‘Piazzotto del Sale’ (‘the little square of salt’), having been commissioned in 1539, by the Dal Corno family, who were official salt sellers in Bassano. The fresco depicts animals and musical instruments, including a monkey and a goat, an image of a naked woman named ‘Truth’ and another of the ‘Drunkenness of Noah’, all painted on the front wall of the salter’s house. As the doors to the windows open and close they reveal or hide ‘Truth’. It would be difficult to believe that the author of these lines had not seen the fresco for themselves.

It is impossible you should see this,

Were they as prime as Goats, as hot as Monkeys,

As salt as Wolves in pride,

and Fools as gross As Ignorance, made drunk.

But yet, I say, If imputation, and strong circumstances,

Which lead directly to the door of Truth,

Will give you satisfaction, you might have’t.

Othello – Act 3 scene 3

Fresco painted in 1539 by Jacopa Bassano – ( now in the local museum)

The town of Bassano offers other clues that lead to William Shakespeare’s work, including mention that the name ‘Otello’ is a common one in the area, yet rare elsewhere, in Italy, and that one of the two apothecary shops, in that ‘little square of salt’, traded under the sign of ‘The Moor’.

A family bearing the Bassano name were musicians and instrument makers in the town, but they left home in 1515, to work for the Doge, chief magistrate and leader of the Most Serene Republic of Venice, in his grand palace. However, by1532, they had migrated to London, as musicians for Henry VIII and the Royal Court. Henry seems to have poached them from under the Venetian ruler’s nose, probably on the advice of one of those visiting English merchants. It is likely this was part of a trading deal between these two, growing, states, so helping to open the floodgates to the tide of English noblemen, who visited the region during the 16th century.

There were five Bassano brothers, who headed for London, in the 1530s, and their offspring continued to be important members of the musical fraternity, throughout the Tudor period. There is a common belief, that the Bassano family had a Jewish background, but this is disputed by some scholars, because Jews were banned from England during this period. However, the evidence looks overwhelming, because of their names, the people they married and the communities in which they lived.

Bassano del Grappa

This first wave of the Bassano family starred as musicians, but later generations branched out into a different field, with three brothers being granted a lucrative warrant, to export calf-skins from England to Venice. This licence, for 100,000 skins a year, was held by the family, from 1593 until 1621. This enterprise may have links to the family’s earlier sojourn in Venice, a city noted for its leather-working, and where the Bassano family still owned property. This trading warrant does lead Stratfordian scholars to suggest a connection with the Bard’s father, John Shakespeare, a dealer in skins, whilst Marlovians connect Kit Marlowe’s shoe-making family with these leather working Italians.

One of the family’s descendants was Aemilia Bassano, (1569-1645) later gaining the surname Lanier, after marriage to a cousin. Aemelia Lanier, perhaps surprising to many readers, is a strong candidate to be the ‘Dark Lady’ of the Sonnets. She was born in Bishopgate, London, the daughter of Baptise Bassano, and at the age of eighteen, became mistress to Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon, who was forty five years her senior. Their relationship began around 1587 and included her begetting a son, who arrived in 1593. This was rapidly followed by marriage to her cousin, Alfonso Lanier, a Queen’s musician, in what seems a union of convenience. The boy’s name was Henry Lanier, and his noble lordship, Henry Carey, continued to deal generously, with both mother and son. It was a year later, in 1594, that Lord Hunsdon became patron of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, who a decade later were transformed into the Shakespeare players, the King’s Men.

Alfonso Lanier’s mother was Lucretia Bassano, daughter of the patriarch of the migrant musicians, Antonio Bassano (1511-1571), born in Bassano del Grappa and died in London. Antonio’s father was Jeronimo Bassano, a first name which rises to prominence, a couple of chapters hence.

After the death of her father, when she was seven, and before being the bedfellow of Lord Hunsdon, Aemelia went to live in the household of Susan Bertie, Countess of Kent, whose mother had been the fourth wife of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. This gives links to Brandon’s third wife, Mary Tudor, (Henry VIII’s sister) and one of those alternative lines of succession. Aemelia received a top class, Humanist education, whilst in the Bertie household, which gave her the skills to become one of the first women in England, to publish poetry.

Later, Aemelia went to live with Margaret Clifford (nee Russell) and her daughter, Anne Clifford, at Cookham Manor, on the River Thames, in Buckinghamshire. Margaret’s eldest sister had married Ambrose Dudley, whilst, quite significantly, their brother, John Russell, had become the second husband of Elizabeth Hoby (nee Cooke), making him the step-father of Edward Hoby, who was, by then, the occupier of Bisham Abbey. Their father was Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford, that political friend of William Cecil and William Cordell, and it is this family that will take us to some of the most interesting places in the Shakespeare story. The Russell clan may even be the leading lights, in keeping the ‘Shakespeare secret’, safe, across the centuries.

Building on a similar, excellent, education, Margaret’s daughter, Anne Clifford, became a patron of authors and literature, and her many letters and a diary gave her a literary reputation in her own right. However, it is in later life that we know Anne Clifford better, as the second wife of Philip Herbert, marrying him in 1630, a year after the death of Susan de Vere, and thus making her, yet another ,Countess of Pembroke, and occupier of Wilton House, during its rebuilding period.

From Bassano to Bisham Abbey and Wilton House – It’s a small world..!

Hunsdon and Aemelia broke up their formal liason, after her marriage, and the dates coincide with the beginning of the performance of plays, later attributed to Shakespeare. Her relationship with Carey brought her into the circle of ‘Oxford wits’ as well as to the notice of the nobles of the Royal Court. Did this Mediterranean beauty become the ‘Dark lady’ of the Sonnets, which may have described the unrequited love of Henry Carey for Aemelia Bassano. Many people think so!

In 1611, Aemelia published her poetry anthology, ‘Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum’ (Hail, God, King of the Jews), only the fourth female poet to publish her own work. Aemelia mentions her conversion to the Protestant faith, probably referring to the common practice amongst the Sephardic Jewish community of openly living as a Christian, but privately retaining their traditional beliefs. The Jewish connection, of course, plays a large part in ‘The Merchant of Venice, and offers more distant links to the Iberian peninsular, the home of the Sephardi Jews, until they were expelled, in 1492.

Shakespeare’s two Venetian plays have characters called Emilia, in ‘Othello’, and Bassanio in ‘The Merchant of Venice’, whilst the Roman tragedy, ‘Titus Andronicus’, has an Aemilius and a Bassianus in the cast. All these pieces fit beautifully together, as I’m sure Lord Hunsdon would confirm..!!

The mention of ‘Titus Andronicus’ leads us to a potential connection to another familiar name, that of James Peele, who had clerical, pageantry and schoolmaster skills, but whose original trade was as a salter. His experiences led him to write two books about Venetian book-keeping, and it was his son, George Peele, who is now acknowledged to have been a co-author of ‘Titus Andronicus’.

We know nothing of James Peele’s life before 1547, except his self-confessed trade as a salter, but just maybe he learnt his Venetian accounting skills in Venice, and had trading connections that took him to Bassano and the home of local salters, the Dal Corno family. As we shall see in a moment, Bassano was one of the last stops on the main land route from Germany and Austria, and on to Venice, but was also a welcoming place for seabourne traders, who could spend some, well earned, ‘rest & relaxation’, in the Alpine foothills, away from the mosquito infested marshes of the Venetian lagoon.

The Italian connection to James Peele might, also, be via one of his two wives. The surname of his first wife, Ann, is unknown, but his second marriage, to Christian Weiders, in 1580, suggests a link to the continent, possibly with Jewish ‘converso’ overtones, as suggested by her ‘Christian’ first name.

It also might just be relevant, that it is the character, ‘Iago’, who shares the scene with ‘Othello’, when the relevant ‘fresco lines’ appear in the script, and as one scholar suggested to me, many moons ago, that ‘Iago’ sounds a little like a Latin version of George Peel’s Oxford friend, William Gager. ’Othello’ was certainly the play that was taken to Oxford, by the Kings Men, in 1610, seemingly to taunt, both the now Puritan leaning university and the town authorities.

Could James Peele be one of those missing Italian jigsaw pieces? That is all a little speculative, but is certainly another of those clues that Miss Marple would put away safely in her writing desk, for possible use later.

Were these plays written from the heartfelt memories of a previous inhabitant of the Italian peninsular, not based on a brief foreign tour or even gleaned from a heavily imbibed Italian merchant in a Thameside tavern? However, the ‘experts’, on both sides of the Authorship argument, seem reluctant to accept a foreign hand on the pen, so where might the author’s expertise in the ways of Italian life been garnered? If that is the case then we need definitive evidence of English involvement in the Italian plays, one that offers an obvious blast of Stratfordian – ‘Forza di volontà’ – That’s ‘Will power’.

That takes us back to one very specific Englishman, one who visited the Italian peninsular from top to toe, journeyed there more than once, and wrote, in some detail, about his travels and the people he met. This man was Thomas Hoby, the diplomat, linguist and traveller, who wrote about his wanderings in a diary cum travelogue, ‘The Travels and Life of Sir Thomas Hoby, kt, of Bisham Abbey, written by himself (1547-1564)’. This book never reached the printers till 1904, but lay as one of a series of manuscripts, at the Hoby home of Bisham Abbey, being purchased by the British Museum, in 1871.

Thomas Hoby died in 1566, so seems unlikely to be the closet Shakespeare we are seeking, but his two sons, Edward (1560-1617) and Thomas Postumous, (1566-1640), both outlived Mr Shakespeare of Stratford, and look to add a few more pieces to help complete the puzzle.

Thomas’ travel book is highly detailed in places, giving an accurate description of the routes taken and of the interesting places he visited. There are also lists of travelling companions and mentions of other English courtiers, scholars, and clerics, who Thomas Hoby encountered along the way. There seems to have been dozens, at times hundreds, of noble and notable Englishmen, all on the loose in Renaissance Italy, particularly during the Marian period, from 1553-1558. One modern catalogue of English students who visited Padua, from 1485 to 1603, lists over 350 individuals, but there were many more.

Researcher, Richard Roe, mapped many of the places that are relevant to the Shakespeare plays, and whilst Hoby mentions most of these, he doesn’t mention them all. Hoby, like many travellers arriving, overland, in northern Italy, passed through the town of Bassano, and spent time in Verona and Mantua.

The most striking link between Roe’s findings and Hoby comes not from the north, but from the linguist’s visit to Sicily, where he mentions in some detail his return trip, by sea, to Naples, via the volcanic, Lipari islands, passing, what Roe believes is ‘Prospero’s Island’ of Vulcano.

Vulcano – Lipari Islands – off north coast of Sicily

Thomas Hoby had many of those important Italian experiences, found in Shakespeare’s Italian plays, but his death in 1566 seems to put him out of the authorship equation, being a generation before the Bard took to his pen. However, his travel book, then only available as a manuscript, was passed on to son, Edward Hoby, a fact we know for certain, because of the copious annotations made in the margins.

However, Thomas Hoby is perhaps better known for another Italian masterpiece, a significant one, at that..!! This is his translation of Baldassare Castiglione’s, Il Libro del Cortegiano, ‘The Book of the Courtier’, which Hoby published, in 1561. Baldassare was an Italian courtier, from an illustrious family, who hailed from Castico, near Mantua, in the Venetian north. It was written over many years, beginning in 1508, and published in 1528, by the Aldine press, in Venice, just before his death.

Hoby’s translation of the book describing the ‘correct’ demeanour of an Italian courtier and gentleman, created a template for the young bucks of Elizabethan England to follow, acting as a precursor to John Florio’s books on language and etiquette. Significantly for Shakespeare followers, the book features characters later found in ‘Much Ado About Nothing’, a play that is set in Messina, Sicily, many leagues to the south.

The Hoby family are at the heart of my family jumble of inter-relationships. Edward Hoby’s mother, Elizabeth Cooke, (Cooke clan) was widowed before the birth of her second son, Thomas Posthumous, and she then married John Russell, son of Francis Russell, Earl of Bedford, one of those recurring families who feature at the heart of the Shakespeare conundrum.

Edward Hoby took as his first wife, Elizabeth Paulet, great granddaughter of the ‘willow bending’ administrator, William Paulet, and for his second wife, married Margaret Carey, daughter of Henry, Lord Hunsdon. This Carey connection makes life more interesting, because Emilia Bassano-Lanier, the ‘Dark Lady’ candidate, and mistress of Henry Carey, therefore, became an unofficial, step-mother-in-law, to Edward Hoby. Add that Hoby/Russell link to the formative years of Aemelia Bassano, who was under the care and tutelage of John Russell’s sister, Margaret, and we see yet another cosy set of relationships, each with a pinch of Italian spice. A third sibling, Anne Russell, married Ambrose Dudley, tying more knots, and adding a link to Warwickshire, and that family of glove-makers.

Like his father, Edward Hoby was a diplomat and academic, and whilst at Oxford University, as a ‘gentleman-commoner’, he had the writer, Thomas Lodge as his ‘servitor’. This was a way of rich man keeping a servant whilst on the campus, and for poor, but academically gifted students, gaining a free education. Hoby made close friends of leading academics, including Henry Savile and William Camden, and if we then add in his relationship to William Cecil, via his mother, and to Queen Elizabeth, by his wife, and we have a man who mixed with the highest echelons of Elizabethan society.

Intriguingly, Edward Hoby took a two year sabbatical from Oxford, in 1576, with the intention of travel to Europe. If he went to Italy, then he almost certainly would have taken his father’s guidebook, so were those notes, in the margins, made from his own observations, and indeed, did he reach places his father had missed? Surely too, Thomas Lodge had read this most singular document, as he was also to become a great traveller to foreign parts, and would have been fascinated by the accounts of Thomas Hoby’s time, journeying across Europe.

Lodge is definitely one of my prime candidates to be a Shakespeare contributor, and could the Hoby travelogue, rather like the Holinshead Chronicles, be where ‘Shakespeare’ gained so much insight into that most romantic of countries. Add this to Messina’s connection to, ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ and Thomas Hoby’s translation of ‘The Courtier’ and this is another family that cant be ignored in any discussion about the Italian influence on the Shakespeare Authorship debate.

Edward Hoby also leads us to another significant figure, that of Henry Unton, whose wonderful portrait has a section devoted to his own travels ‘sur le Continent’. Twenty years after Henry Unton had died (1596), whilst ambassador in Paris, his sister, Cecilia Unton (1561-1618) became Edward Hoby’s fourth wife. Just ‘another’ family connection many would say, but another which suggests these two families were closely allied.

So, Henry Unton, a man I believe is more important to the Shakespeare saga than anyone realises, is another with a strong aroma of basil and oregano about him, and he is also to reappear later, as we move northwards to our French connection. Here is a man who possessed all the first hand experiences we hav been searching for, and a man who died at the moment the name of ‘William Shakespeare’ was to enter the scene, as a writer and to take possession of his new home in Stratford.

Another candidate, whose Italian credentials seem to have been overlooked, is Anthony Munday, (1560-1633) one of Henslowe’s favourites and one who is now an accepted co-writer of parts of the Shakespeare canon. Like George Peele, Munday remains a recurring figure, throughout this story, and because he lived through the entire Shakespeare era, he is a prime candidate to be one of our editors-in-chief. His strength as an author was in updating old plays, and this became his forte when Philip Henslowe became his paymaster, from 1597 onwards. Munday was known as the ‘poet of the City’ and one of the most productive writers of the period.

Munday’s youthful experiences had taken him to France and Italy, and particularly to the Jesuit run, English College, in Rome. His travels began in 1576, after abandoning his apprenticeship with printer, John Allde, and headed for Europe. He stated that he travelled to learn about the people and to learn new languages, but he was also one of those keen-eyed ‘tourists’, feeding back information as part of Elizabeth’s spy network. He remained abroad for over six years, and during that time worked with the English ambassador in Paris, and claimed in a letter he wrote to Edward de Vere, that he had visited Rome, Naples, Venice, Padua and ‘diverse of their excellent cities’.

Anthony Munday is, of course, one of the Coleman Street gang, and one of four men who Henslowe credited with co-writing the ‘Life of Sir John Oldcastle’. This was printed ‘anonymously’ in 1600, but appeared under the name of ‘William Shakespeare’, in the ‘false folio’ of 1619. If we need to find a Shakespeare candidate with all the right Italian credentials, then look no further than Anthony Munday. However, with a portfolio overflowing with work, there seems very little reason for him to take on a covert identity, unless it was at the behest of one of those noble lordships, who wanted to keep schtum.

So, could our Italian writer be an amalgam of reminiscences, recorded by a number of English travellers who had visited the most popular and romantic of Elizabethan tourist destinations. Italy was in the blood of the Tudor traveller and it is at the heart of the works of William Shakespeare. Where the two meet is still open to great debate, but surely that discussion would be UNLIKELY to include the son of a leather trader from Stratford-upon-Avon, even if he held a reader’s ticket for the local library.

American researcher, Richard Roe determined that ten of Shakespeare’s ‘fiction’ plays were set, at least partly, in Italy and notes that only one of the Bard’s ‘fictions’ has a setting in England, a ratio of 10:1, a little odd for England’s greatest writer… don’t you think?

Well Roe does and I think I have to agree.

So, which of the plays are we talking about, and how do they relate to the printing and publishing, particularly the role of Edward Blount and his sixteen entries on to the Shakespeare scene.

Richard Roe’s Ten Italian plays

Romeo and Juliet Two Gentlemen of Verona

The Taming of the Shrew Merchant of Venice

Othello (act one) All’s Well That End’s Well

Much Ado About Nothing The Winter’s Tale

The Tempest

Plus, perhaps surprisingly, to many students of the Bard: ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’.

The author set the ‘Midsummer’ play in Athens, Greece, but Roe moves that location to Italy, calling it ‘Midsummer in Sabbioneta’. This is a small town, near Mantua, and bears the local name of ‘Little Athens’ and has a Temple and a Duke’s Oak, which exactly complement the Shakespeare play.

Roe also noted that there were three plays set in Ancient Rome; ‘Coriolanus’, ‘Titus Andronicus’ and ‘Julius Caesar’, each with a classical theme, but which might offer interest in any discussion of Italy.

Three of these ten plays are of the five credited to the ‘fair copy’ work of Ralph Crane, four out of six if you also credit Crane with ‘Othello’. These three, ‘The Winter’s Tale’, ‘The Tempest’, and ‘Two Gentlemen of Verona’ are also part of Edward Blount’s cache of sixteen plays, the ones that may have been performed, but were never published until 1623.