Chapter 5

William Shakespeare – first sightings

–

Will Kemp – actor and comic dancer

‘Let those that play your clowns speak no more than is set down for them’ (Hamlet).

–

William Shakespeare – at last..!!

The words of William Shakespeare are on the school curriculum in almost every country on the planet and he is one of the most famous names in history. Billions of words have been written about the ‘great man’ and his works, and the analysis and criticism doesn’t seem to be abating. A Hollywood film was released in 2011, suggesting that William of Stratford didn’t write the works attributed to him, and this was immediately met with a flurry of indignation from those who are convinced believers in the legitimacy of the author. My impression is that the most vociferous defenders of his reputation tend to be those whose livelihoods depend on the status quo being maintained.

With the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death upon us, there will be a further rise in the temperature, as literary scholars, the media and the general public, clamour to celebrate this significant milestone. His anniversary will see sales of his works given a boost, and so the gloves will be off in the battle between his supporters, who I call the ‘Stratfordians’ and the ‘doubters’, some may call ‘conspiracy theorists’, commonly known as the ‘anti-Stratfordians’.

My journey into the realm of Shakespeare has brought me into contact with a variety of his admirers, from the ‘great and the good’ of the literary and theatrical world, on to scholarly academia and finally to people like myself, who have started some simple local history or family research and ended up in the arms of the Bard of Avon.

These various commentators seem like decent, honest, often highly educated people, but almost all avoid taking a ‘broad brush’ approach to the subject, but stick to the minutiae. Acknowledged experts in the field have actively discouraged me from taking a wide approach. I have always found that attitude quite strange, as addressing the ‘big picture’ is an essential component in understanding any project. This is especially so when the researcher is trying to unravel the complications of centuries of learned conjecture, mixed in with a measure of conjugated detritus. This is a cat’s cradle of the first order..!!

Established academics tend to approach the discussion from a specific direction and their musings frequently try to justify their beliefs. Academics also strongly believe that supporters of the Bard don’t have to prove the status quo, but any deviation from that entrenched position has to be backed up with evidence of the highest order, coupled with a bibliography of gargantuan proportions. This is not a level playing field, as Stratfordians continue to want to play the game downhill, with the wind at their backs and the referee in their back pocket.

The other glaringly obvious necessity for anyone who wishes to commentate on anything with the name ‘Shakespeare’ appended, is that this must be done in hushed tones and with a certain degree of reverence. Any attempt to do otherwise is treated with disdain, contempt and regarded as an unworthy piece of research. We are dealing with a ‘national treasure’ here so charlatans, conspiracy theorists and those without a raft of academic qualifications must stand well clear. ‘Mind the doors please..!’

Some of the ‘small time’ authors, who actually have new and refreshing things to say about William Shakespeare, talk about being afraid to speak their mind on the subject, just in case it upsets the academic community. This sense of fear has even spread to liberal, free-thinking, literary academics themselves, those who want to openly challenge the status quo, which is being perpetuated by their single minded colleagues. This seems akin to becoming acquainted with the rules of an exclusive Gentleman’s club in Mayfair, or perhaps an august Scottish golfing institution, with admission only available, to the ‘right sort of person’.

The whole subject of Shakespeare, the man and his works, is thus treated with a religious reverence by the ‘clergymen’ of the literary world, who see it as their job to guard its rituals and secrets. This is rather at odds with the welcome sign at the gate to Stratford’s Holy Trinity, a parish church that claims to be the most visited in England. Here, they also do their best to maintain the sense of mystique and theatre, which surrounds their great literary figure.

In all these billions of words of praise and criticism, the fact and the fiction, the real man and his stories, all seem to get jumbled together. One eminent expert comments on another’s analysis, and if they are of some repute, then this goes on the record as being a definitive truth. I have read material that is third, fourth, fifth, even twentieth hand, and when I trace the reference back to the earliest source, I often find the original premise is woolly in the extreme. The experts’ cast iron journals aren’t quite as well founded as they believe.

The creativity of Shakespeare’s supporters, the Stratfordians, often out-performs the works of their hero, himself. The very few words written about him, by his contemporaries, have been turned into countless chapters and volumes of extrapolation and explanation, often just pure fiction. In my own family’s copy of Shakespeare’s Works, the ‘Henry Irving’ edition of 1899, the introduction by Henry Glassford Bell puts the situation quite succinctly. Bell describes how experts on the subject, ‘fringe an inch of fact with acres of conjecture, many of the facts of which are self-evidently false’.

One of the first people to suggest that William Shakespeare wasn’t the author of the works attributed to him was the Reverend James Wilmot, who in 1780 scoured Warwickshire seeking tangible evidence of the Bard’s existence. After searching in vain, failing to find even a snippet of physical evidence, and covered ‘with the dust of every private bookcase within fifty miles of Stratford’, he decided to destroy his notes, fearing that news of his lack of evidence would reach the outside world. However, Wilmot did tell a friend about his misgivings, but these doubts only emerged when the friend’s papers were discovered, some 150 years later, in 1930.

The first person to pose the authorship question in print was Delia Bacon, an American writer who was convinced Shakespeare was a pseudonym for a group of men who had fallen out of favour with the Royal Court. She included Francis Bacon, Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser amongst her suspects.

Whenever Delia Bacon and Francis Bacon are mentioned together in this context, there is nearly always a footnote by the author, saying the two Bacons are not related. Has anyone checked, as this seems to be an untested assumption? If the genetic work of Bryan Sykes is to be believed, there has to be a good chance that they are related, if someone was to look back through history? Her grandfather was a church missionary, working with the native, American Indian population, but the family must have migrated from England at some point.

Delia was followed very shortly afterwards by William Henry Smith, who proposed Francis Bacon as the sole author of Shakespeare’s complete canon of work. Both Delia Bacon and William Smith published their work in 1857 and since that time over 5000 contentious volumes have reached the shelves of booksellers like W.H. Smith & Sons; about two every month for over 150 years. Yes, in case you are wondering, the Shakespeare sceptic was also the famous bookseller, William Henry Smith.

Many doubters, the ‘anti-Stratfordians’ have been prominent figures; respectable writers, actors and scholars of their era, but even these luminaries have become the subject of ridicule and scorn. Those that don’t agree with the perceived wisdom have been described as; ‘eccentrics of the most familiar type or wealthy old gentlemen safely indulging a latent hunger to be radical about something.’

Perhaps, there should be a crime of ‘Shakespearean literary heresy’, with the punishment being burnt at the stake in the main square, outside the Stratford Memorial Theatre, fuelled with copies of the author’s own satanic work. I have already felt the ridicule of the Stratfordians, after communicating my findings to some of the leading lights on the subject. My eyes are now wide open, my back covered and my old friend, Barney McGrew, is permanently on standby with his fire engine.

I have also felt the criticism of the flailing tongue of supposed colleagues, in the battle to unearth the truth about the Stratford mystery man. In fact, the doubters can be just as extreme as the Stratfordians. There seems to be very little neutral ground between the two sides.

Plays and poems

With most authors there is a simple, well established chronology to their work, with little doubt about what they wrote or when they wrote it. Newcomers to the Shakespeare genre would expect mountains of documentation and cross-referenced data, but this is William Shakespeare the most famous and yet the most mysterious writer in history. There are so many questions, and rarely do two scholars come to agree on any of the answers.

One reason for the uncertainty is that literary documentation in Elizabethan times was chaotic in the extreme. The performance of a play had to meet the approval of the Master of the Revels, who was the official censor, appointed by the monarch, working under the auspices of the Lord Chamberlain. This was a system of government approval, but matching the name of the play to the content and assigning an author to the work was not an exact science. Plays often had a change of title or the name of the author was not mentioned. Plays also tended to evolve over time, as performances became polished.

The publishing of literary works had to undergo a different process. Plays and poems were supposed to be registered with the Stationers Company, but many never were or those that appeared on the record might not appear in print until years later. Again the names of plays changed between editions and many were recorded without an author.

Thirty six plays were included in the 1623 folio, with eighteen of them published under Shakespeare’s name for the first time. Later folios, published in 1632, 1663, 1664 and 1685, include amendments to the original plays, with an extra tranche being added to the compendium, in 1664. It is these later folios, that were regarded at the time, as ‘new improved’ versions, which add to the confusion. The Bodleian library, in Oxford, sold their 1623 edition, to replace it with the enlarged, ‘director’s cut’, 1664 version, so this esteemed body was as confused as everyone else.

There are two other, pre-1623, collections of work that are attributed to the Stratford man, and both produced by publisher cum printer, William Jaggard. In 1599, he published a collection of poems entitled the ‘Passionate Pilgrim’, which had ‘W. Shakespeare’ named as the author, although on closer scrutiny, the anthology had a variety of named and anonymous contributors. Jaggard reprinted these poems again in 1601 and twice in 1612.

In 1619, Jaggard also printed what has become known as the ‘false folio’, when ten ‘Shakespeare’ plays were bundled together into one volume. William Jaggard certainly seemed to know who his target was, but many scholars take a similar view to that of George Swinburne, who in 1894, described him as an ‘infamous, pirate, liar and thief’, making the family,‘rogue printers’, intent on just making a quick groat or two.

Little did George Swinburne know…!!

Nothing could be further from the truth……. read on..!!

There is a little help in the dating and attribution of Shakespeare’s work from Frances Meres, who listed twelve plays under Shakespeare’s name, in his ‘Palladis Tamia’, or ‘Wits Treasury’, of 1598. This is a rambling summary of the works of Elizabethan playwrights and poets, and Meres comments on the specific strengths of numerous writers, listing them in a loose pecking order.

Palladis Tamia – 1598

Royal Court and other official records also offer a source of dating, as they mention performances at significant state events. Generally though, despite hundreds of years of exhaustive scholarly study, the extent and timing of Shakespeare’s literary canon is still a matter of fierce debate.

The earliest evidence of the plays appears from 1592 onwards, but these were in performance only, without attribution to an author, and not yet in print. Indeed, there is no play attributed to Shakespeare, by name, until 1598. Of course, the plays could have been written much earlier, and there is one group of anti-Stratfordians, who suggest they were written a decade prior to their emergence on the stage.

In theory, it ought to be clear what Shakespeare wrote, and what he did not. Surely the plays included in the ‘First folio’ must belong to Shakespeare, because those contemporary compilers were in the best position to know. The printers, Jaggard & son, had been involved with the Shakespeare name over a number of years and so they ought to have known what was genuine and what was not. However, their 1619 folio contained three plays that were not contained in the 1623 ‘official’ edition and many Stratfordian scholars doubt whether two of the three were written by Shakespeare, at all.

So which version was correct?

Literary scholars have long questioned the Jaggards’ credibility in their dealings with the Shakespeare canon and some are bemused how the perpetrator of earlier, what they now regard as scurrilous, unapproved, piratical work, could end up winning the contract for the official version. I leave that till later, because my revelations about the Jaggards will open up whole new lines of enquiry. Indeed the Jaggards might not be the ‘problem family’ frequently mentioned, but rather offer help in finding a solution to this whole mystery.

The Jaggard legacy continued on through to the later folio editions, printed decades later, and these ‘rogues’, also have connections to a number of other creations, attributed to Shakespeare. The ‘apocrypha’, as it is known, are the works not in the 1623 folio, but which have appeared at various times with Shakespeare’s name attached. Modern scholars now pass judgement, on these ‘extras’, which skirt around the edges, and the Juke Box Jury panel of ‘Oxbridge’ literary experts has enough confidence in their ability, to declare them a genuine ‘hit’ or a ‘miss’, 400 years after the event.

There are various theories about how these other offerings arrived at the table. Fraudulent printers seem to get the lion’s share of the blame for most things, whilst more generous commentators suggest that the apocrypha may have been collaborations with other writers, or earlier works that were overlooked by the King’s Men, the company who gained the sole rights to perform Shakespeare’s plays and were able to control their publication.

There are over twenty contentious plays, including several which appeared during Shakespeare’s lifetime and with his name firmly stamped all over them. One of the most interesting is ‘Sir John Oldcastle’, which was originally published by Thomas Pavier, in 1600, with no named author. However, in 1619 the play was attributed to Shakespeare, when it was re-published as part of the ‘false folio’ project. The plot thickens because, theatre owner, Philip Henslowe records in his diary that the play was written jointly by Anthony Munday, Michael Drayton, Richard Hathwaye and Robert Wilson. Surely, in this situation this clear conflict of attribution should sound alarm bells for everyone involved in the debate.

‘A Yorkshire Tragedy’ was published in 1608, credited as the work of Shakespeare, and although not seen fit to be included in the 1623 version, appears in the revised, second edition of the Third folio, in 1664. Many scholars now give Thomas Middleton the credit for this play, but I offer other options.

‘Two Noble Kinsman’ was not published until 1634, being credited as a collaborative effort between William Shakespeare and John Fletcher. This generally gets the thumbs up for authenticity from modern scholars, but it never made an appearance in any of the five folio compilations.

‘Edward III’ was a play originally published anonymously, in 1596, and was only attributed to Shakespeare in a bookseller’s list, some fifty years later. Some scholars credit Thomas Kyd with at least part of the content, but the Royal Shakespeare Company has performed the play in recent years, because it has many hallmarks of their hero.. ‘Edward III’ does seem to be a crucial play in any discussion about the authorship question, because if it had been included in 1623, then few scholars would have challenged its authenticity – but it wasn’t.

There is a smattering of consensus about which plays came first, but there is still no certainty. That honour is fought out between one of the ‘Henry VI’ trilogy, ‘Richard III’, ‘Titus Andronicus’ and ‘Two Gentleman of Verona’, but exactly when they were written or in which order is hotly debated.

The Henry VI trilogy started life as three separate plays, each with very different names, probably written Henry/2, then Henry/1, as a prequel, and finally Henry/3. It is commonly thought ‘Henry VI/2’ might have been the first ‘Shakespeare’ play, but ‘Two Gentleman of Verona’ also has its supporters.

No single publisher or printer was used by Shakespeare and there is no consistency of bookseller either. The rights to publish and print plays were, often, transferred between the various commercial entities, so the path from the stage to the printed page was rarely a straightforward one. Some of the printed material is of dubious quality and there seem to be a number of pirated and incomplete versions. Nothing is clear and simple. There are dozens more points of discussion and with some plays the debate about authenticity gets far more air time than the play itself.

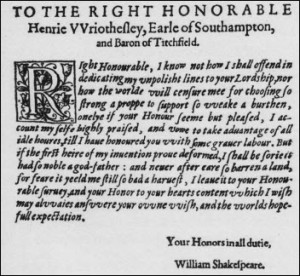

However, the first appearance of the name William Shakespeare, anywhere in literature, was associated with poems not plays. ‘Venus and Adonis’, a love poem based on Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ was registered anonymously with the Stationers’ Company on 18th April 1593, and printed by Richard Field, later that year. This poem contains a dedication, made by William Shakespeare to the Earl of Southampton, and is the first mention of his name attached to a piece of literature.

The following year another poem appeared in print, this one with a much darker theme. The ‘Rape of Lucrece’ was registered with the Stationers Company on 9th May 1594, and printed later that year, again by Richard Field. This poem takes a lead from work by classical writers Ovid and Livy, and has similarities to one of Shakespeare’s earliest plays, ‘Titus Andronicus’. Again this poem was registered anonymously and Shakespeare’s name was only attached in the form of a second dedication, again directed to the Earl of Southampton.

Dedication attached to the ‘Rape of Lucrece’.

THE LOVE I dedicate to your lordship is without end; whereof this pamphlet, without beginning, is but a superfluous moiety. The warrant I have of your honourable disposition, not the worth of my untutored lines, makes it assured of acceptance. What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have, devoted yours. Were my worth greater, my duty would show greater meantime, as it is, it is bound to your lordship, to whom I wish long life, still lengthened with all happiness.

Your lordship’s in all duty, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE.

Both these poems were registered anonymously, and significantly in the original editions, Shakespeare’s name is not attached to the poems themselves but only to the dedications. (Later editions did carry the Stratford man’s name.) Writers of the period frequently dedicated their work to their benefactors or even potential sponsors, but there is no evidence of reciprocation between the two men.

However, here we find one of many unfounded ‘truths’ that have entered the Shakespeare biography. Over a hundred years after the event Nicholas Rowe wrote, in 1709, that “There is one instance so singular in the magnificence of this patron of Shakespeare that, if I had not been assured that the story was handed down by Sir William D’Avenant, who was probably very well acquainted with his affairs, I should not have ventured to have inserted; that my Lord Southampton at one time gave him a thousand pounds to enable him to go through with a purchase which he heard he had a mind to.”

£1000 was a small fortune in Shakespeare’s day and payments for poems often amounted to only a pound or two, perhaps £5 for a play. This seems to be an unlikely embellishment to the Shakespeare saga, aimed no doubt, to raise the kudos of the author?

Science to the rescue…?

As well as literary experts, historians and scientists have done their best to help answer the authorship question. These various disciplines have sough the truth by analysing the one million words which make up the complete Shakespeare text and apocrypha. Literary experts have looked at the development of the style, looking for typical signs of a maturing author. They have also compared every word and phrase with those of contemporary authors, and have checked for source material, earlier books which might have given Shakespeare his ideas. Every literary stone has been upturned, perhaps ten thousand times, but still questions seem to outnumber the answers.

Historians have tried to match the content of Shakespeare’s work to the political and social events of the period and this has helped to confirm the order in which the plays were written. This dating method helps a little, but is often compromised by supporters of a particular alternative candidate, who desire to match the plays EXACTLY to the biography of their man. Of course supporters of the status quo likewise try to match the dating evidence to the period, 1564-1616.

Scientists are now using the powerful memory chips of 21st century computer technology, to analyse Shakespeare’s portfolio. Research is slowly leaking out, but has not, yet, provided the definitive, single author answer, which the majority of literary historians seem to demand. Recent results complicate rather than simplify the picture, and some of these are discussed later, when looking at rival candidates.

Twenty five years ago, in the early days of computer analysis, Ward Elliott and Robert Valenza, studying at Claremont McKenna College in California, compared a selection of Shakespeare’s poems and plays with those of fifty eight contemporary authors. The pair of American statisticians took a sample of Shakespeare’s sonnets, poems in plays, and the plays themselves and broke them down into standardised word blocks. Their methodology comes in for criticism today, but mainly because it didn’t produce the answers those critics desperately seek.

The Californians’ results turned out to be quite conclusive, as Shakespeare’s words and phrases came out of the tests as very different to his contemporaries. The closest match was for explorer, Walter Raleigh, but he only had a two per cent chance of him being the author of Shakespeare’s entire canon. The study particularly focussed on the Earl of Oxford, as he was the bookies favourite in the 1990s, and is the one still making the running today.

Elliott and Valenza’s findings:

‘We found Shakespeare’s patterns to be strikingly consistent, and often strikingly at variance with those of other Elizabethan poets. A cross-check of each conventional test against 3,000-word samples from an early Shakespeare play (Richard III) and a late one (Macbeth) indicates very little change in Shakespeare’s profiles, apart from line endings. The old Shakespeare seemed just as likely as the young to pour out hyphenated compound words, to stint on relative clauses, and to write at a given grade level. In general, Shakespeare used compound words and open and feminine endings more frequently than his contemporaries and relative clauses less frequently.’

‘Our conclusion was that Shakespeare fits within a fairly narrow, distinctive profile under our best tests. If his poems were written by a committee, it was a remarkably consistent committee. If they were written by any of the claimants we tested, it was a remarkably inconsistent claimant. If they were written by the Earl of Oxford, he must, after taking the name of Shakespeare, have undergone several stylistic changes of a type and magnitude unknown in Shakespeare’s accepted works.’

The Earl of Oxford, the bookies favourite, is given a very hard time, and comes out as a no-hoper. The idea of a collaborative work also didn’t gain favour with the researchers. Consistency is the word that jumps out of the report, and the authors wondered how a ‘committee’ could provide that consistency. The Californians suggest the author is probably one person and conclude that this must either be the man Shakespeare himself, or a total newcomer on the block, a person that has not previously entered the discussion.

Creating Shakespeare by committee

What seems obvious to me, and is mentioned by an increasing number of commentators, is that ‘Shakespeare’ could well be the product of a co-operative venture. This seems to be the only solution that makes complete sense, when you take into account all the ponderables. Yet, the analysis, by tens of thousands of scholars, and by that Californian research team, shows a remarkable consistency of writing. So much so, that certain plays are discounted by modern literary scholars, as definitely not attributable to the Bard, despite having his name firmly attached to them during his own life time.!!

Even amongst the anti-Stratfordians, the strongest advocates are very much for the ‘single persona’ theory, and few can comprehend how it is possible to persuade a group of free thinking authors to write as one coherent brand name.

In fact, the group dynamic is the norm in modern creative writing for the television screen. Books are, generally, written by single individuals, but many of the most successful television ‘light dramas’, are created by partnerships of two people, and in the case of innovative comedy during the 20th century, frequently by groups of writers, often in a seemingly unregimented environment.

Ground breaking comedy fits that pattern, with the Goon Show, Cambridge Footlights and Monty Python, each working off a strong group dynamic. Then there was that huge list of American screenwriters that seemed to roll on forever, in the final credits to ‘Rowan and Martin’s Laugh In’. This used to bring a smile to the British audience, even if the jokes seemed less than funny, to the more sophisticated natives, living on this side of the pond.

Successful single comedy writers are rarer and often the very best exhibit personal flaws. Stephen Fry and Victoria Wood have openly expressed doubts about their own literary abilities, whilst Ronnie Barker, who I regard as one of the most creative wordsmiths of my lifetime, was so unsure of his writing skills that he donned the persona of ‘Gerald Wiley’, keeping the secret long into his acting career. In what was an ‘ensemble’ scriptwriting team, many of the funniest sketches of the ‘Two Ronnies’ and all the trademark communal songs were contributed by the reticent, ‘Gerald Wiley’.

Writers such as Alan Bleasedale, Alan Plater, Dennis Potter and Alan Bennett, working at the more serious end of popular drama, tend to prefer their own company. Much of their output is personal and emotional and sometimes with a strong political or social message. They have been praised for the realism shown in the literary portraits they paint, but their work has been criticised strongly, by those who hold different political views. In other regimes and in earlier generations, all might well have experienced the inside of a prison cell, for openly expressing such individualistic views, which challenged the government policy of the day.

Literary critics have a tendency to want to give labels to writing genres, but often comedy and tragedy are two sides of the same coin, with some of the best writers managing to mix the two, almost seamlessly. When David Renwick was asked why his hit comedy series, ‘One Foot in the Grave’, often had extreme moments of violence and melancholy, he responded by saying, probably with a little tongue in cheek, that he had never thought of the program as a comedy show! Shakespeare’s plays demonstrate that same strong mixture of tragedy and comedy, with the odd romantic touch thrown in for good measure.

However, the question posed by the Californian analysts was how is it possible to get such literary consistency from a diverse group of people, writing under one name. Well, this is how it could be done and I know because, at one point, I was an integral part of such an ongoing literary operation.

One of my tasks as a training specialist, working for an international pharmaceutical company, was to compile and update the medical manuals, which were used to train our 200 sales people. Two or three of the training department always had a ‘manual’ project on the go, and with plenty of new products being added to the portfolio, it was always one of the first jobs given to a new member of the team.

When I got down to the task, it soon became obvious this was not just an extended essay and that I was not merely an author, but a project manager. The task seemed daunting in the extreme, because I had never written a training manual before, indeed, I hadn’t written anything longer than a sports report for a local newspaper, since my time at university.

I quickly realised, there was a very strict formula and all the manuals had a similar look and feel to them. It was also clear there had been several rebirths of the original format, so not only was it important to retain an overall style, but also necessary to keep abreast of the latest educational trends.

Despite my paucity of experience, there was plenty of guidance available from colleagues, plus there were ten manuals in regular use, and many more on the dusty archive shelves, all to be used as guides and comparators. Each section of the manual needed specialist content,, which had to be scientifically accurate and verifiable. To be assured of the accuracy of the technical detail, I was going to have to rely on the input of qualified doctors from our medical department, and a variety of medical journals.

The company was also obsessive about its image, which meant they demanded consistency of literary style for all written material, both formal publications and even simple memorandums to colleagues. These were the days before personal computing and email, which meant that every typed letter and document, produced in the company’s name, had to be ‘signed off’, by at least one line manager.

Finally, there were the guys with the red pens, two ex-Fleet Street proof readers who were notoriously good at their job. Their guide to uniformity was a thick glossary that ensured a world wide standard was maintained, all the way from Hoddesdon to Honolulu. Punctuation, numbers, capital letters and layout were all covered in the bulky tome. My first humble offering, a simple one paragraph letter to a regional manager, was returned with a laugh and more red marks than I had words on the page. I learnt quickly and a week later, I was almost red line free and close to their idea of ‘acceptable’.

Each section of the training manual had to be signed off by my head of department, and this was then passed around to the other section leaders, who had a vested interest in my work. The whole process sanitised my efforts, removing my personal idiosyncrasies, and kept the writing and content at the required standard. It was an unforgiving process and so by the end, my completed manual looked like all the others. Yes, it was really my piece of work, I wrote every word, although my name did not appear on the finished item, just the trademark of the company.

So, could a similar process have been used to create William Shakespeare’s plays? Does the pen-name, ‘William Shakespeare’, really have to be one person or could it be the pseudonym for a collective of Elizabethan writers, produced, in not dissimilar fashion to my corporate training manuals?

The original format for Elizabethan plays would have been the starting point of the process, one that was provided by the classical authors of Greece and Rome. The ‘Seneca’ play had a strict format, and there were also ‘Aristotle’s rules’, which were seen as a model for all playwrights.

Therefore, writing to strict guidelines was nothing new to the classically educated writers of Tudor England. Some writers had been brave enough to develop this further, to reflect the more liberal Renaissance mood, but there were still unwritten rules and overall Elizabethan writers adhered to an accepted formula.

Members of a ‘Shakespeare playwright team’ would need some agreement to moderate their writing style, but as with my own experience, the co-operative system brought us together to write with one ‘voice’. If the plays were being produced in a workshop situation, in the convivial surroundings of a grand house or university, then this convergence would happen naturally.

Imagine a group of literary friends together in a grand Tudor drawing room and you have the beginnings of a successful writing ensemble.

This corporate approach was clearly explained by the actor and director, Mark Rylance, at a conference to discuss the ‘authorship question’. He said that different writers have different strengths; ‘some are good at plot, others at characterisation, whilst others adept at timing, humour or the mechanics of stage production’.

Finally, there would need to be a proof reader or editor, someone that acted like a shearman in the textile industry, removing the unwanted bits and pieces, smoothing the text, and who signed off the work before it was handed over to the actors. This would be the ‘William Shakespeare’ figure, the editor-in-chief, and that position might have changed hands over the twenty plus years of the project, something suggested by a change of style in the later plays.

Whilst some authors kept their own ‘fair copy’ notebooks, it is likely that the finished work was dictated and that a scribe did the writing. Employing a copywriter, seems to be an essential part of any ruse. It was no good attempting to be incognito if your handwriting was all over the work. This would explain why not a single word has been found in the authenticated ‘hand’ of William Shakespeare.

The text could certainly be influenced by the final copywriter, the man who wrote out neat copies of the original scribblings and ensured a consistency of grammar, spelling and punctuation. He was the equivalent of my Fleet Street men with the red pens, but he may have had a little extra input, and yes even the Shakespeare diehards accept this might have happened, but with their man as the main author.

The majority of the people, who I believe were involved in the Shakespeare conspiracy, worked as government officials, foreign ambassadors, had secret lovers, or were simply members of that political cauldron, the Royal Court. Passing covert messages and keeping their identity secret was an everyday part of the lives of so many of these individuals. For most courtiers, ‘covert’ was their middle name, and for those caught out, a heavy fine or even a visit to Tower Green was their potential reward.

Indeed, at the same time Shakespeare’s plays first appeared on the stage, there was already a major co-operative work underway. The King James Bible, eventually published in 1611, was the culmination of a 20 year project and the work of forty seven of the most learned and religious men of the period.

This was a translated work, not a totally creative one, but it was important to maintain a house style, one that kept the writers speaking with a single voice, all the way from Genesis to Revelations. On completion, their great Bible, like my training manuals, was published anonymously.

Interestingly for my story, the only member of the translation team, who wasn’t a member of the clergy, was Henry Savile. He was a Greek tutor and mathematician at Oxford University and the leader of a four year journey around classical Europe, which included visits to Vienna, Venice and Verona and from Paris to Padua. Quite coincidentally, Henry Savile was born on a rather inconsequential family estate, just a couple of miles from Halifax… at Bradley Hall, Stainland..!!

View halloo….?

Like so much about Shakespeare’s literary life, there is great debate about when his name was first mentioned as an author. His name is clearly associated with the two poems, ‘Venus and Adonis’, registered in 1593, and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’, in 1594. Both were originally printed by Richard Field, in London, not long after the poems had been registered with the Stationers Company. Field adds extra colour to the story, because he was, ‘by chance’, also a native of the same, Warwickshire town, as the Bard, himself.

As we saw earlier, there is a separate page of dedication attached to each poem, and these are addressed to the 21 year old, Earl of Southampton, by the signee, William Shakespeare, although there is a slight look of a 1960’s, ‘John Bull printing set’ about the addition of his name at the bottom. Shakespeare’s name does not appear directly attached to the poems till later editions were published, and their original registration with the Stationers Company makes no mention of an author’s name.

However, there is a strange reference to a ‘hyphenated’ Shake-speare in another poem, which was registered on 3rd September 1594, very soon after the ‘Rape of Lucrece’ must have been published, as it was only registered, a few weeks earlier, on 9th May. This poem, published as a pamphlet, was titled, ‘Willobie his Avisa’, the story of the wooing of a woman called Avisa, by H.W., who sought advice from W.S ‘the old player’, a previously unsuccessful suitor of the same old maid.

The poem is believed to have been written by Henry Willobie, a native of West Knowle, in Wiltshire, who was an undergraduate at St John’s College, Oxford, from 1591 to 1595, a man who would have been living amongst those Oxford ‘wits’ , who appear, regularly, throughout my saga.

The poem is interesting in several ways, all of which are relevant to the Shakespeare story.

At the end of one stanza there is the phrase ‘And Shake-speare paints poore Lucrece rape’, which is clear reference to the freshly published poem, dedicated to the Earl of Southampton. Some scholars speculate that Willobie is also referencing Shakespeare, in his use of the initials, W. S., and that the H.W. might refer not to himself, but to Henry Wriothesley (the Earl of Southampton).

Curiously, in 1596, Henry Dorrell wrote an ‘apology’, (an explanation of the story behind the poem), which seems intended to create a smokescreen around the ‘Avisa’ poem. Dorrell said the author, Willobie, had ‘now of late gone to God’, and his poem had been written 35 years earlier. Most of Dorrell’s ‘apology’ seems like nonsense, as Willobie was born in 1574 and died in 1596 and ‘Lucrece’ had only been published just days before the Avisa poem must have been written.

If Dorrell is correct, and the ‘old player’ is really ‘old’, then Willobie was not the author, and so we are dealing with another pseudonym, one that was invented to challenge that of the name ‘William Shakespeare’, which appears on the two dedications to the young Earl of Southampton.

The refusal to wed a number of suitors, suggests that the maiden, Avisa, may be intended to represent Queen Elizabeth – and that idea is strengthened because Elizabeth’s personal motto was ‘Semper eadem’, (always the same), and the heroine of the poem signs her letters ‘Alwaies the same, Avisa’

This was obviously a satirical work, intended to mock the use of Shake-speare’s name and to use Avisa as a caricature. Eventually there reached a tipping point, because an entry to the Stationers’s Register dated 4th June 1599, says that ‘Willobies Adviso’ is to be ‘Called in’, which indicates the pamphlet was censured, and probably to be burned. However, that wasn’t the last that was heard from ‘Avisa’, as the pamphlet was reprinted several times more, after the death of Elizabeth, in 1603.

Clearly, there are word games being played between the intellectual elite of Oxford, and the courtiers, represented by the Earl of Southampton, and at the heart of it all is Good Queen Bess. No-one has yet contrived a suitable explanation for these literary shenanigans, but it is the first time that Shakespeare’s name is written as Shake-speare, suggesting that there was a plot afoot to use the name of a man from Stratford-upon-Avon, in a clandestine way. Note too that date, 1596, the year of the ‘apology’, which I believe is the most significant year in this whole Elizabethan melodrama.

Overall, this simple pamphlet rather muddies the waters rather than produce a crystal clear stream of understanding. If this was intended to be a parody of Elizabeth’s love life, why did the censors wait for five years before banning the work. Previously the punishment for questioning the Queen’s decision making had been swift and more draconian to the perpetrators, be they writer, publisher or printer.

When the Shakespeare conundrum is finally exposed to sun drenched daylight, I’m sure ‘Willobie’s Avisa will make sense, but till then it can be put to one side, as one of Poirot’s unexplained clues.

BUT – these are poems, and there is no written connection between William Shakespeare and any of ‘his’ plays until 1598. So, to fill that time gap, the Stratfordians need something more substantial to support their cause and hold back the growing tidal wave of anti-Stratfordian sentiment. Their single straw in the wind and a single crumb of comfort, is the word, ‘shake-scene’.

The hyphenated word appears in a letter, written by the author, Robert Greene, who died in 1592, at the very beginning of the ‘Shakespeare era’. ‘The word, ‘shake-scene’ and other confirming lines are part of a posthumously published letter that was addressed to three friends and fellow poets, Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe and George Peele, to whom Greene administers a ‘gentle reproof’ and offers advice as to how to move forward with their lives.

Green admonishes Marlowe for being a non-believer in God, whilst to Nashe, he suggests he lightens his verse a little and write a comedy, and to Peele; he says he has more talent than the others, and not waste time writing for the theatre.

Even these few lines by Greene, written to friends and colleagues, aren’t as simple as they might be. The letter is contained in a work entitled; ‘Greenes, Groats-worth of Witte, bought with a million of Repentance’, published by author, printer and publisher, Henry Chettle, ostensibly, as the work of the ‘recently deceased writer Robert Greene’.

This work, attributed to Greene, is a compilation of poems and prose with much revision and addition by Chettle, and was entered at Stationers Hall on 20th September 1592. How much is Greene and how much Chettle is still hotly debated, but there is clearly a fair smattering of both.

‘Base minded men all three of you, if by my miserie ye be not warned; for unto none of you, like me, sought those burrs to cleave; those puppets, I meane, that speake from our mouths, those antics garnisht in our colours. Is it not strange that I, to whom they all have been beholding, shall, were ye in that case that I am now, be both at once of them forsaken? Yes, trust them not; for there is an up-start crow, beautified with our feathers, that, with his Tyger’s heart wrapt in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you; and being an absolute ‘Johannes Factotum’, is in his own conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrie’. ‘But now returne I againe to you three, knowing my miserie is to you no news; and let me heartily entreate you to be warned by my harme. For it is a pittie men of such rare wits should be subject to the pleasures of such rude groomes.’

…. ‘the upstart crow…….. the only Shake-scene in the country’.

The Stratfordians, almost without reservation, take this to mean Greene is addressing his three friends and making reference to Shakespeare, who MUST be the ‘upstart crow’.

Nearly a century ago, William C. Chapman, a Canadian scholar, expended several thousand words analysing these ‘shreds of evidence’, which the Stratfordians hold so dear and Chapman pulls to pieces the suggestion that the phrase ‘shake-scene’, has anything at all to do with William Shake-speare.

The connection between ‘shake-scene’ and Shakespeare was never a contemporary one, but made over a century later, when the study of his plays became popular. Thomas Tyrwhitt (1730-85), seems to be the first to make a connection and this is now treated by ‘Stratfordians’, as one of those ‘irrefutable facts’ that cannot be challenged, but without any evidence to support it.

Chapman suggests the ‘upstart crow’ is NOT Shakespeare at all, but clearly identifiable as William Kemp, the celebrated comic actor, jig-dancer, and jester, who was in his own admission, the ‘only shake-scene in a country’ – referring to his abilities as a comic jig-dancer.

Will Kemp became established as a leading actor in the Elizabethan theatre, during the 1580s, but also acted the clown and for many theatre-goers his dancing jigs, accompanied by comic words and music, were the highlight of the entertainment.

Kemp was a popular performer as early as 1589, and was in the habit of not sticking to the script, making him unpopular with the playwrights, whose work he spouted with such gay abandon. His performances wouldn’t have been out of place at a performance of the ‘Good Old Days’, at the City Varieties Music Hall, in Leeds, or perhaps a 1950s ‘End of the Pier Show’, at Margate.

Will Kemp, in his only published pamphlet, ‘The Nine Days Wonder’, written in 1599, turned upon his high brow critics, and in retaliation, called them ‘shake-rags’. Shakespeare was an unknown and unheralded name in 1592, whilst Kemp already had a growing reputation. So, Chapman believes the face of William Kemp fits far better than William Shakespeare, on the photo-fit of the ‘upstart crow’.

The final nail in the ‘shake-scene’ coffin, is that there is no mention anywhere of William Shakespeare as an actor, writer or theatre owner during Robert Greene’s lifetime, so any connection between the two is unrecorded, and would not seem worthy of note, in such a cryptic way.

More poems

Shakespeare’s poems are regarded as a major part of his writing and reputation and one particular format of poetry, the sonnet, goes hand in hand with the ‘Shakespeare’ name. The connection between the sonnet format and Shakespeare was first established in William Jaggard’s ‘Passionate Pilgrim’, an anthology of twenty poems attributed on the front cover to ‘W. Shakespeare’, although inside there are a variety of credits to other poets, including several with none – ‘anon’.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets, numbers 138 and 144 appear for the first time in ‘Passionate Pilgrim’, but after due consideration, although Jaggard, quite clearly credited Shakespeare with 13 of the 20 poems, the jury of experts now attribute only five ‘hits’, to the alleged author.

The next mention of Shakespeare, allied to a piece of poetry, is the mysterious allegorical poem that appears in an anthology of poems, under the title, ‘Loves Martyr or Rosalins Complaint’.

It was ‘imprinted for E.B’ in 1601; the publisher being Edward Blount, who 20 years later had his name, writ large, on the front of Shakespeare’s First folio. The printer was Richard Field, who had been the printer of ‘Venus & Adonis’ and ‘Rape of Lucrece’. This anthology was never registered with the Stationers Hall, but the author of the main poem appears to be an unknown poet, Robert Chester.

The ‘Phoenix and the Turtle’, are the subjects for ‘Loves Martyr’, an allegorical tale that includes the story of King Arthur. This is thought to allude to another of Queen Elizabeth’s failed love affairs, her favourite brooch being the Phoenix jewel. The single poem, commonly attributed to William Shake-speare, also takes the ‘Phoenix and Turtle’ theme. Poems by the other named contributors, Ben Jonson, George Chapman, John Marston, also follow the same theme.

However, I am going to attract plenty more controversy here because on reading a facsimile of ‘Loves Martyr’, it doesn’t seem to reflect EXACTLY, the sections attributed to William Shake-speare. Almost all current texts give a title to the work, but in my facsimile copy, there is NO title – it just begins:

LET the bird of loudest lay,

On the sole Arabian tree,

Herald sad and trumpet be,

To whose sound chaste wings obey.

This is then followed by thirteen further stanzas, each with four lines and a rhyming pattern; abba.

There is no author mentioned at the bottom of this page..!!

On the next page there is a new poem, blocked by a woodcut, top and bottom, which bears the title:

‘Threnos’, (meaning lamentation).

Beauty, truth, and rarity,

Grace in all simplicity,

Here enclosed in cinders lie.

Death is now the phoenix’ nest;

And the turtle’s loyal breast To eternity doth rest,

Leaving no posterity:

‘T was not their infirmity, It was married chastity.

Truth may seem, but cannot be:

Beauty brag, but ’tis not she;

Truth and beauty buried be.

To this urn let those repair

That are either true or fair;

For these dead birds sigh a prayer.

The attribution to William Shake-speare appears at the bottom of the ‘Threnos’ page, and in my understanding of the layout of the pamphlet, this does not relate to the poem on the previous two pages. ‘Threnos’ is short and simplistic, in the extreme, with a rhyming scheme that wouldn’t be out of place in the notebook of a ten year old ‘apprentice’ poet, not one attributed to the world’s greatest writer…??

The style and content of the longer poem, which most scholars attribute to Shakespeare, doesn’t bear his name, nor does it fit any of the other work attributed to the great Stratford poet.

It looks to me that modern scholars have got it horribly wrong – the first poem being a total irrelevance and that the short and simplistic, ‘Threnos’ poem has been written by another of the anthology’s contributors, possibly Ben Jonson, included as an in-joke amongst those in the know, thereby ridiculing the fakery of the Shakespeare brand, following on from the ‘mustard’ reference in 1598.

***

However, the bulk of Shakespeare’s poetry is contained in the 154 sonnets, which were first published , in its entirety, in 1609. The sonnet is a poem of fourteen lines, ending in a rhyming couplet. The name ‘sonnet’ means ‘little song’ and had its origins in the south of Italy, during the 13th century. The format moved north, to Tuscany and Venice, where the English were frequent visitors in the 16th century.

Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard were the first Englishmen to use the sonnet style and the ‘little song’ appeared in print for the first time in England, in 1558, as Tottel’s Miscellany of ‘Song and Sonettes’. The form was not used again until it was adopted by Philip Sidney in the 1580s and then a decade later when 23 of the 79 poems in the ‘Phoenix Nest’ anthology, published in 1593, used the ‘sonnet’ format. In later centuries, many of the great English poets used the sonnet form, including William Wordsworth, John Milton and my namesake, Robert Browning.

There is mention, by Francis Meres, that a number of Shakespeare’s sonnets were being circulated amongst the ‘smart’ set, in coffee shops and taverns, during the 1590s, but apart from the two which appeared in the ‘Passionate Pilgrim’, there is nothing to offer a clue as to when they were composed.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets were first published in 1609, by Thomas Thorpe, but there was an additional poem added to that volume, entitled, ‘A Lover’s Complaint’. This poem comprised forty seven stanzas, each of, seven-lines, but written in ‘rhyme royal’, the same metre that had been used in ‘Rape of Lucrece’. Modern day experts regard this additional poem as very ‘un-Shakespearean’ and probably not connected with the person who wrote the ‘Sonnets’. Again doubts are being raised, even by Strafordians, and here are more ‘expert’ judgements being made in the modern era, on work that clearly says ‘Shakespeare’ on the cover..!!

Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnets’ ought to have been a popular work amongst the dandy courtiers of the period and to prove the point, the ‘Passionate Pilgrim’ was reprinted in 1601 and 1612, (twice). However, after its initial release, in 1609, the Bard’s sonnet anthology seems to have gone into hibernation, for a number of years, with no mention by contemporary sources, and no reprint made until 1640.

Then, the ‘little songs’ re-appeared in a different format, as ‘Poems: Will. Shake-speare, Gent’, published by John Benson of St Dunstan’s Churchyard and printed by Thomas Cotes, printer of the Second folio of 1632. Benson rearranged the sonnets into groups, added titles and generally tampered with the original concept of the 1609 version. Poems by other writers, associated with the Shakespeare canon, were also added, and six original sonnets were omitted. Benson may have felt freedom to edit the original volume because Thomas Thorpe had died in 1635, causing the copyright to lapse.

1609 edition Benson’s 1640 version

Shakespeare’s sonnets seem to be autobiographical, and a very personal record of the feelings of one person towards others, famously with mention of a ‘fair youth’, the ‘rival poet’, and the ‘dark lady’. The dedication at the beginning of the original, 1609, edition is framed in a pyramidal format and addressed to ‘Mr W.H.’. Many readers regard the dedication itself as cryptic and the mystery of ‘Mr W.H.’ has still not been solved and has brought dozens of suggestions as to the owner of these initials.

The case has been made for lovers (of both sexes), a variety of noble lords and the publisher’s financial sponsor, with the intriguing dedication, itself, being analyzed by everyone, from code breakers in Cheltenham to the crossword experts of the Waterloo & City line. This puzzle-solving exercise is one where every contestant seems to believe they have found the correct solution, despite the vast array of answers being proffered to the panel of adjudicators, no prizes have yet been awarded

One novel suggestion, and one which appeals to me, because of its simplicity, is by American Shakespeare theorist, Alan Tarica. In his treatise, ‘Forgotten Secret’, Alan has made a strong case for reversing the order of the original 154 poems, then reading them in sequence from 154 to 1. You might say he has turned Shakespeare on his head.

Sonnet 154

The little Love-God lying once asleep,

Laid by his side his heart inflaming brand,

Whilst many Nymphs that Vow’d chaste life to keep,

Came tripping by, but in her maiden hand,

The fairest votary took up that fire,

Which many Legions of true hearts had warm’d,

And so the General of hot desire,

Was sleeping by a Virgin hand disarm’d.

This brand she quenched in a cool Well by,

Which from love’s fire took heat perpetual,

Growing a bath and healthful remedy,

For men diseased, but I my Mistress thrall,

Came there for cure and this by that I prove,

Love’s fire heats water, water cools not love.

This would seem to read as an introduction to a sequence of poems, not the end, whilst the reverse is certainly true of Sonnet ‘Numero Uno’, which could easily be read as a melancholy finale.

–

Sonnet 1

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s Rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’st flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl makest waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

Alan Tarica is a proponent of the idea that the Earl of Oxford wrote the Sonnets, as a secret correspondence with his lover, the ‘virgin’ Queen, Elizabeth. He postulates that the poems are a plea from Oxford to Elizabeth that their ‘love-child’, Henry Wriothesley (the Earl of Southampton) should be made her successor to the throne of England. This might seem far too much ‘conspiracy’ rolled up into one story, but covert references to Elizabeth’s inability to find a mate, litter the writing of the period, and may well have inspired the creation of the Shakespeare pseudonym.

I make the point because there is plenty of innovative thinking which surrounds the work of ‘Mr Shakespeare’, but most is actively ignored by those who think they know better. Here, by simply reversing the order, a new meaning is revealed, and without the need to decipher complicated codes. Is Alan Tarica right or wrong about the deeper meaning of the Sonnets? I have no idea, but his theory does make more sense than many that have gained far greater prominence and given more credence by mainstream Stratfordians.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets, instead of being simpler to unravel than the plays are actually just as complex, continuing to ask questions at every level. Nothing is simple – from the pen first hitting the paper, through to the dedication, the relevance of the order of the poems, and finally to their later printing and distribution. The plays are a mystery, the poems are a mystery, the publishing and printing of his works befuddles many learned minds, and so what about the man himself?

Barney McGrew and his mates – on hand to help – just in case I have upset someone..!!

–

Chapter Six

Shakespeare – the man

The Bard’s Biography

The simple biography of William Shakespeare, the one I was taught at school, talked of a clever man, even a genius, who was the greatest playwright and poet of the English speaking world. He was said to be born in Stratford-upon-Avon on 23rd April 1564 and died in the town, on his birthday, in 1616. His father was a glovemaker and after marrying Anne Hathaway, Shakespeare moved to London and became a writer. Shakespeare was also an actor and a part owner of a theatre and a complete collection of his plays was published, posthumously, in 1623. He is also famous as a poet, writing the ‘Sonnets’.

There isn’t too much detail, but all the ‘facts’ seem to be correct. I could have mentioned that William’s father, John Shakespeare, was Mayor of Stratford, and his mother was Mary Arden, from a distinguished Warwickshire family. ‘Will’ wrote poems and three types of plays; history, comedy and tragedy. Ben Jonson was another famous writer of the period and the two playwrights would frequently be found discussing literary and theatrical matters in one of London’s taverns. William Shakespeare’s nickname was the ‘Bard of Avon’ and in his will, he left his ‘second best bed’ to his wife.

That’s a total offering of nearly 200 words, which seems rather basic information about England’s greatest writer. There must be a multitude of books written about his personal life, his family and his career as a writer. Where is the detail? Well, if you visit Stratford-upon-Avon today, you will find a whole industry based around these few simple facts. No more, no less.

Shakespeare in Stratford – here, there and everywhere..!! – photo KHB

Despite this wafer thin biography, William Shakespeare’s plays and poems are on the curriculum of every education system across the planet and his name must be in the ‘top ten’ most famous names of all time. The Bard’s collected works, along with the Holy Bible, are included as essential reading on the BBC Radio program, Desert Island Discs, making an assumption that everyone would want to take them to their paradise isle.

Yet, 150 years ago, the famous American author, Mark Twain, was sceptical whether there was a scrap of evidence to prove, even the existence, of a man called William Shakespeare. Rather bizarrely, Mark would debate this issue with an old steamboat pilot, who was training the future writer, to take on that responsible role, of navigating a safe passage through the sandbanks of the Mississippi River.

Mark Twain

It was another 50 years before Twain published his thoughts on the subject, in his book entitled: ‘Is Shakespeare really dead?’

‘Isn’t it odd, when you think of it: that you may list all the celebrated Englishmen, Irishmen, and Scotchmen of modern times, clear back to the first Tudors; a list containing five hundred names, shall we say. You can add the details of the lives of all the celebrated ecclesiastics to the list; all the celebrated tragedians, comedians, singers, dancers, orators, judges, lawyers, poets, dramatists, historians, biographers, editors, inventors, reformers, statesmen, generals, admirals, discoverers, prize-fighters, murderers, pirates, conspirators, horse-jockeys, bunco-steerers, misers, swindlers, explorers, adventurers by land and sea, bankers, financiers, astronomers, naturalists, claimants, impostors, chemists, biologists, geologists, philologists, college presidents and professors, architects, engineers, painters, sculptors, politicians, agitators, rebels, revolutionists, patriots, demagogues, clowns, cooks, freaks, philosophers, burglars, highwaymen, journalists, physicians, surgeons; you can get the life-histories of all of them but ONE. Just one, the most extraordinary and the most celebrated of them all; Shakespeare!’

Mark Twain is of course correct, because when the tangle of 400 years of celebrity is cleared away, there is very little left of substance, apart from a very scratchy biography and the plays and poems themselves.

Footprints in the sand

Not only is Shakespeare one of the most famous of all Mark Twain’s ‘names’, he is also the most widely researched. Generations of scholars have avidly sought more information about the great man, but although a trickle of new material has been uncovered about his personal life, there is nothing new to support his credentials as a dramatist. Many have tried, but the success rate hovers close to zero.

Writers have long used pseudonyms to hide their identity and Samuel Clemens is one of the better known, prominent amongst a list that includes the Bronte sisters, George Elliot and Lewis Carroll. There must be a multitude of reasons why an author doesn’t wish to attach their real name to their own work, but Clemens was somewhat of a comedian, and his first use of the name, Mark Twain, was just a bit of escapist fun. This was just one of a number of different names he attached to his early work, when a cub reporter with his local newspaper. Insecurity may have been part of his initial motivation to use pseudonyms, an emotion felt by many creative people, when offering their work to public view.

Agatha Christie was her own name, but the famous writer of detective fiction, used another personna, that of Mary Westmacott, when writing romanctic novels. Harry Potter author, J.K. Rowling, took the same avenue, creating a new personna, when she followed Christie in the other direction, trying her hand at detective fiction, rather than the world of child magicians.

Many other use a ‘false’ name because they are fearful of the political or social consequences of challenging authority or even just the social conventions of the day. This was, indeed, very much the situation in Shakespeare’s time, as government laws and social conventions dominated all aspects of life. To make things more complicated, the rules might change in a trice, as monarchs and subsequent allegiances often changed with the swing of an axe.

Modern autobiographies are, increasingly, being written by ‘ghost writers’, especially when the ‘A list’ storyteller has limited literacy skills. Here the dictated words of the celebrity and the scribblings of the real author become inter-twined, so it becomes difficult to tell them apart. Most published material is actually an amalgam to some extent, as the proof reader or sub-editor wields the red pen of correction and deletion.

Surely, though, the expectation has to be that any author (noteworthy or otherwise) would wish to be associated with his work at some point. Both the heralded and the anonymous writer would inevitablyt leave a trail of personal and literary footprints throughout their writing career. My own contribution to the William Shakespeare debate contains a plethora of autobiographical material, which includes snippets from my earliest days, and then onwards, to shape my present day view of the world.

A few literary tracks I would expect to find with any writer:

Education commensurate to their literary skills.

Variety of life experiences, reflected in their work.

Literate family environment, parents, siblings, children.

Travel experiences reflected in literary content.

Survival of ‘other’ written material; short notes, letters to friends & family.

Original manuscripts written in the author’s hand.

Literary ability mentioned by friends and family in their own letters.

Unfinished manuscripts, notes, etc, found after death.

Mention of own literary work in own will and testament.

Recognition during lifetime, by place of birth or place of abode.

Dedications to family and friends on published work.

Family show interest in literary work, especially after death.

The list is long and certainly not inclusive of all the possibilities. Famous playwrights and authors of the last 100 years might not tick every box, but the ones I have perused seem to tick most of them.

Noel Coward, Tom Stoppard, Alan Bennett, Arthur Miller, Alan Plater, Alan Ayckbourn, Frank Muir, W.H. Auden and Harold Pinter were writers in various genres, which I have checked in some detail and all have clear literary and personal biographies. I then, quite randomly, chose other names from a Wikipedia list of international authors, none of whom I had previously heard about. The list included Vasile Alecsandri, Ugo Betti, Nick Enright, Max Frisch and Jack Gelber – but I soon got bored with the exercise, because the picture was identical every time, their lives and works were easily detectable, albeit to a greater or lesser extent.

The majority of these great writers hailed from wealthy, privileged or literate backgrounds, but there was a minority who found literary fame from illiterate, poor or rather discouraging homes. The disadvantaged ones seized their opportunity at some point, often with the opportunistic help of a friend, relation, tutor or mentor, who championed their attempt to express themselves on the printed page.

All tended to begin their writing in a small way and developed their skills with age. Once they had begun to write, they all left clear trails, showed development in their work and left a few tangible pieces of paper to show they really had put pen to paper. My list is not exhaustive, but the creative writer who ticks the fewest boxes, leaving little or no trail at all, is William Shakespeare.

I have often heard it said that a writer’s first work is almost always autobiographical, and for many authors, all their writing is based on personal experiences or based around people they have known. Charles Dickens based his wonderful characterisations on real people, and Arthur Conan Doyle did the same, with his great detective character, being an amalgam of friends, colleagues and included large traits of himself, in both Holmes and Watson.

Dr Joseph Bell, the Edinburgh doctor, (left) inspiration for Conan Doyle’s great detective

Indeed, autobiographical tracks must, surely, be a clue to the provenance of any author’s output. Is there such a trail in Shakespeare’s great works? Well, amongst nearly one million words you would expect there must be a clue to the author’s identity in there somewhere. Of course there is, but does that trail lead back to Stratford-upon-Avon or should we be looking for inspiration somewhere else?

William Shakespeare and his Dad

Mark Twain doubted even the existence of a man called William Shakespeare, but I feel confident there was such a person, although whether this man had any literary skills, I have become, very much, a ‘Doubting Thomas’.

The quantity of evidence has increased a little since Mark Twain’s time, as more documents are discovered in the dingy basements of libraries, legal store cupboards or the recesses of county record offices. More is now known about William the man, and his family, than appeared in my brief schoolboy summary, so here is an updated, extended version of the ‘official’ evidence.

William’s father, John Shakespeare, was probably born about 1530, and certainly by 1552, he was living in Henley Street, in Stratford-upon-Avon, where he was fined by the local council for failing to remove a pile of horse dung, from in front of his house. This was the first of several brushes with the authorities, which John Shakespeare had during his life, and it is this tranche of legal records which provide the most conclusive evidence about the existence of John, Mary, William and the family.

John Shakespeare married Mary Arden, although we don’t know when or where, as parish registers were not routinely kept during the Marian period (1553-58). The suggestion by historian, Michael Wood is that they married in 1556 or 1557, possibly at Aston Cantlow church. Mary had inherited land at Wilmcote village (a couple of miles outside Stratford), from her father, Robert Arden. He was a member of a prominent Catholic family and she was the youngest of eight daughters, by Robert’s first marriage. John Shakespeare proved to be an astute businessman, which he demonstrated in his choice of trade, his choice of friends and his choice of marriage partner.

The Stratford parish records only began in 1558, at the time when Elizabeth took the throne after the death of her Catholic sister, Queen Mary. It has always been supposed that John and Mary Shakespeare’s first two children were Joan and Margaret, born in 1558 and 1562. Both died a few months after their birth and the first to survive infancy was William, born in 1564, and baptised on 26th April. An outbreak of bubonic plague hit the town that following summer, so William and his family were lucky to avoid being one of 250 victims of the disease, which took about a fifth of Stratford’s population.

Shakespeare traditionalists have always celebrated his birthday on 23rd April, which is St Georges Day, and very conveniently for the patriotic types, is the patron saint of England. Traditionally, St George’s was the Catholic feast day when artistic merit was celebrated and dates back to medieval times.

Two centuries earlier, on St George’s Day, in 1374, Geoffrey Chaucer, another great English writer, was rewarded for his literary efforts with a ‘gallon of wine, daily for life’. The Shakespeare marketing department couldn’t have done a better job, if they had actually chosen the date themselves..!

British stamps to commemorate the 400th birthday, in 1964.

John Shakespeare’s political star rose quickly during his first years in the town. He held several responsible positions in the newly created, Borough of Stratford, being elected ‘aletaster’ (the weights and measures inspector) in 1556, constable in 1558, chamberlain of Stratford in 1561, voted an Alderman in 1565, High bailiff (mayor) in 1568 and Chief Alderman, in October 1571. He was obviously a trusted and successful member of the community during these years.

During John Shakespeare’s advancement through the ranks, more children arrived. So, Joan, born 1558, Margaret; 1562 and William; 1564 were followed by Gilbert, 1566; Joan, 1569; Anne, 1571; Richard, 1574 and Edmund, 1580, all clearly recorded in the Holy Trinity church register.

However, in the early 1570s, John Shakespeare had several brushes with the law, charged with illegal wool dealing and money lending. His involvement with usury probably began as an extension of his trading business, but also because of his association with the Combe family, who were also in the same unsavoury occupation. Despite Henry VIII legalising usury, in 1545, the whole principle of money lending was regarded by the Protestant and Catholic churches as immoral and by the population at large, as a dubious business. John also made an application to the College of Heralds, to bear his own coat of arms, but his application, made in 1570, was eventually rejected.

Researcher, Donato Colucci, a professional magician (!!!) by trade, suggests a sequence of events which explains John Shakespeare’s rise to fame, followed by his meteoric fall. From 1578 onwards, the family came under severe financial pressure, as John failed to pay his taxes for ‘Poor Relief’ and Mary’s inherited lands, including ‘Asbies’ at Wilmcote, were mortgaged.

Colucci’s study of the original records for Stratford Borough, found that John was originally apprenticed to master glovemaker, Thomas Dixon, who owned the bespoke Swan Inn. The innkeeper did well, so he ‘passed’ his leather business to John Shakespeare, an enterprise which included the preparation and trading of animal skins, and the bleaching process, known as whittawing.

After 1565, John diversified his business, adding wool dealing and money lending to his portfolio, so making his main occupation that of a ‘brogger’, a middle man (wholesaler) dealing in wool. Brogging was a very lucrative occupation, taking much of the profit that had originally gone to the yeoman and tenant farmers. Wholesaling in wool was taxed, from 1552 onwards, with the intention of dissuading participation in the business, but the regulations were rarely enforced locally.

John Shakespeare was warned by local magistrates, in 1569, for charging £20 interest on a loan for a partner to purchase wool, and in the early 1570s was, himself, charged with illegally purchasing wool. Usury and brogging would explain how John became a rich and successful man, but Colucci thinks he has discovered why the business suddenly nose-dived in spectacular fashion.

On 28th November 1576, Queen Elizabeth made a proclamation, that because of excessive exporting of wool to Europe; ‘no licensee shall buy any wool until 1st November 1577’.

This meant the ‘official’ wool trade was halted for nearly a year, but this also ensured that unofficial ‘broggers’, like John Shakespeare, were affected, with only Merchants of the Staple being able to trade in wool. The law was rigorously enforced the following summer (1577), at sheep shearing time, and to discourage any attempt to break the regulations all ‘wool traders’ were bonded to deposit the substantial sum of £100, with the local court, as a guarantee against any indiscretion. The government placed much of the blame for the problems in the wool trade on the shoulders of the dealers in animal skins, who had illegally moved into the wool trading business. The regulations were specifically aimed at people like John Shakespeare.

John attended the Stratford council meeting on 5th December 1576, but was marked absent at the next one, held on 23rd Jan 1576/77. He remained away from the council from then onwards, failing to pay as dues as an Alderman, in 1578. The lucrative side of his business was in ruins and he and the family must have been forced to return to their leather and tanning business, which might also explain his possible diversification into butchery. Things got even worse, because, in 1580, John was fined £40 for failing to appear at a debtor’s court case, and for much of the next decade he regularly seems to have been in financial difficulties and unable to pay his dues. John Shakespeare was finally struck off the council list of Alderman in 1586, having not attended the meetings for ‘many years’.

William Shakespeare’s school days?

So, William Shakespeare was the offspring of successful parents whose prosperity came to an abrupt halt during his early teenage years. John Shakespeare’s trade and civic position in the town should have given his boys access to the King Edward VI Grammar school, situated next to Hugh Clopton’s Chantry Chapel, in the centre of Stratford-upon-Avon. There had been a school on the site since the 13th century, but it became the very last of Edward VI’s endowed grammar schools, chartered at the same time that the town was given borough status, and only days before the young King died, in 1553.

These were not totally new schools, but upgraded and re-branded with the King’s seal of approval, and granted the right to display the Tudor Rose. Education was conducted entirely in Latin with long, twelve hour, days, which provided a high standard of education for those lucky enough to receive it.

Was Will, a pupil at Stratford Grammar School, or helping his father, prepare the skins?

Supporters of Shakespeare’s claim to be a writer, the Stratfordians, assume William must have attended this school, because if he was the author of thirty six plays and a multitude of poems, then at some stage in his life he needed to have acquired the skills and knowledge to have written them. There are no school records for the period, and there is no evidence to show that William, Gilbert, Richard or Edmund Shakespeare, were ever in attendance. It seems logical to us that John, a senior town official, would educate them to a high standard, but most children were set to work from the age of six or seven, especially if there was a family business to run.

Illiteracy was the norm in the population as a whole, and that shortcoming also reached the higher echelons of society. The sudden collapse in the family fortunes, when William was aged twelve, puts in grave doubt whether he or his brothers attended school after 1577, as all hands would have been needed to support father’s failing enterprise.